Pictured above is the Canyon Creek bridge along the Green Mountain forest road. It and the road beyond were damaged in 2011 and has remained closed ever since. Each year its condition degrades further making any eventual repair/replacement even more expensive. Meanwhile, the bridge closure rendered the remaining 8.5 miles of Green Mountain road inaccessible to vehicle traffic. This transformed the already challenging Three Fingers Lookout trail from 4,200ft and 15mi to a highly committing 5,300ft and 26mi putting it out of reach for all but the most dedicated and skilled hikers. Despite being closed for 13 years, there is little hope for repair and reopening. With each passing year the continued degradation of the road most likely means the loss of access to this area of the Cascades forever.

Even more unfortunately is that this is far from a unique story. The access to trails that thousands of recreational mountain-goers in the Cascades all rely on is slowly eroding due to lack of maintenance on our forest roads. Areas of the Cascades are either becoming considerably more difficult to visit or lost entirely as roads become washed out, closed, and simply never repaired. What’s more, this further exacerbates the overcrowding problems as more people are funneled into the smaller number of trailheads that remain with sufficient access.

Why is this though? It’s not due to any malicious desire to purposefully restrict access but rather one core issue: lack of funding. Specifically, this article aims to explore the history of how our forest road network came to be, the current state of the network, its likely future, and potential mitigations to avoid its continued degradation.

Scope

A short note on the scope of this article and the organization of the USFS: Unlike other government agencies that manage federal lands such as the National Park Service (NPS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) which are under the authority of the Department of the Interior, the Forest Service is under the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). This is a somewhat unusual arrangement and it means that policies, budgets, and priorities may diverge between the USFS and NPS, among others.

As such, this article focuses nearly exclusively on the USFS rather than the NPS. The latter is an entirely different topic with an entirely different set of needs, budgets, and maintenance backlogs which is outside the scope of the analysis performed here.

How did we get here?

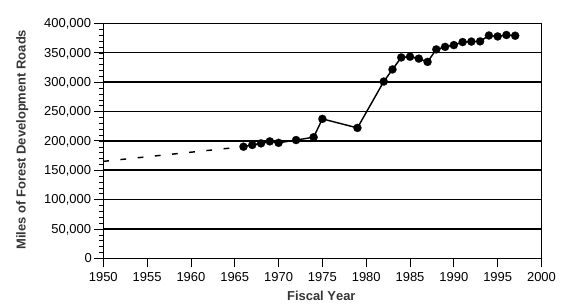

To start, it’s safe to say that the forest road network was built on the back of the logging industry of decades past. Absent it we would not have even a fraction of the forest roads that we currently do. Forest roads were rapidly built to support logging operations after WWII through to the 1980s. Afterward, growth virtually stopped in the 1990s corresponding with the decline of the logging industry thus leaving us with essentially the forest road network we know today.

Size of forest road network over time 1

Size of forest road network over time 1

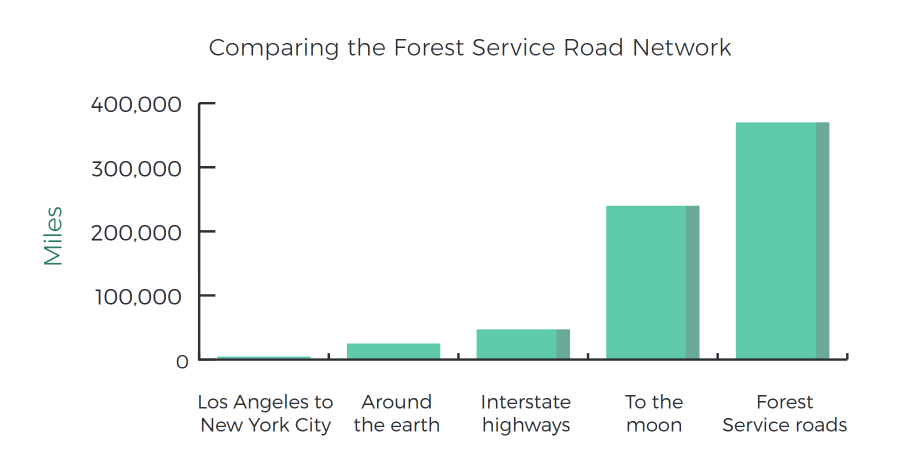

The end result of this construction being a total network size of approximately 375,000 miles of forest roads nationwide.1 It’s difficult to comprehend just how massive this network is. To put it in perspective, the forest road network is eight times the size of the entire interstate highway system. In fact, 375,000 miles is greater than the distance to the moon!

Forest road network size comparison 2

Forest road network size comparison 2

It truly is a massive road network. So how, then, was it built?

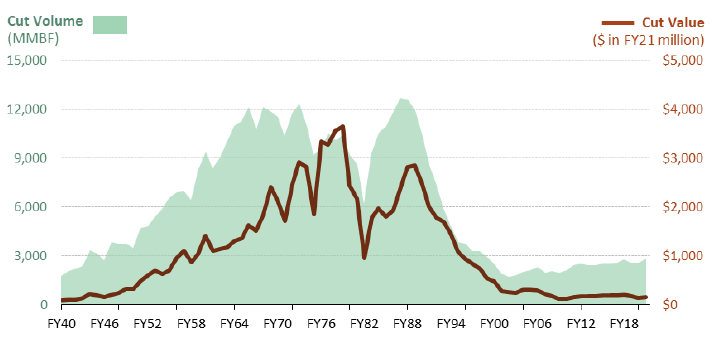

Prior to WWII, most of the US timber supply was generated from private forests. At that time National Forest land only supplied 2% of US timber. After WWII, this percentage grew as the Forest Service began to raise harvest limits in the 1950s. Harvest rates peaked in the early 1990s before beginning to decline.3 Today, logging levels are a fraction of their peak and back to pre-1950s levels.

Logging over time 3

Logging over time 3

To understand the implications of this expansion and its subsequent decline we need to understand what timber receipts are and how they fund forest management. In short, timber receipts are money paid by logging companies to the Forest Service for the rights to harvest timber from federal land. These timber receipts in turn go back to the Forest Service as funding for forest management, including, but not limited to, road maintenance. There are a few broad categories this funding goes to: 4

- The Knutson-Vandenberg Act of 1930 mandates that a certain amount of proceeds from logging be used for reforestation and forest management. The exact amount will vary depending on the needs of a specific area to be cut, but is generally around 25%.

- 25% goes to the state the logged forest is located in.

- 10% is contributed to the Roads and Trails Fund for road and trail maintenance.

- Roads built for the purposes of logging by the logging company are eligible for credits against the owed timber receipts. In other words, a new road’s construction costs are deducted from the owed receipts stemming from its logging operations.

- Any remaining funds are sent to the general fund of the US Treasury.

The end result being that during the decades when the logging activity in National Forests was high there was a large amount of funding for forest road maintenance being generated through timber receipts and incentives for logging companies to build new roads by deducting their construction costs from the owed receipts. Accordingly, as logging in National Forests rapidly declined during the 1990s so did the revenue collected from timber receipts. Consider exactly how much funding was lost between the 1990s and today:

| Year | Gross Timber Receipts | Roads Funding |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | $1.9B | $195M |

| 1985 | $558M | $56M |

| 1990 | $1.6B | $161M |

| 1995 | $369M | $37M |

| 2000 | $187M | $19M |

| 2005 | $248M | $25M |

| 2010 | $136M | $14M |

| 2015 | $200M | $20M |

| 2019 | $186M | $19M |

Roads funding over time 5

We can see from those numbers that, on average, 10% of timber receipts went back to road maintenance and repair. Today, the overall funding from this source has declined by upwards of 90% from its peak in the 1980s and 1990s.

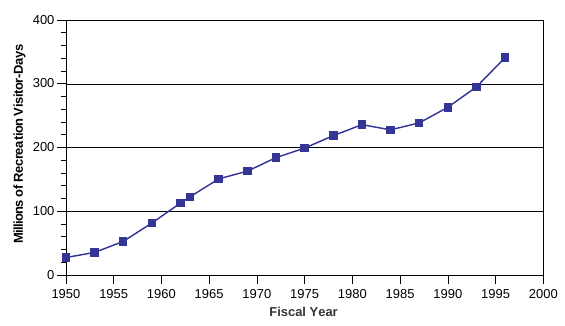

Despite this funding drop for maintenance, as of the 1990s the amount of recreation use in the national forests has climbed by 1,400% from 1950s levels, and is surely considerably higher today.

Forest recreation use over time 1

Forest recreation use over time 1

Budgets & Appropriations

Such a large decrease of road funding would make the future of these roads seem bleak. There’s more to this story than the decline of timber receipts, however. For a deeper understanding, we must delve into the exciting world of federal budgets!

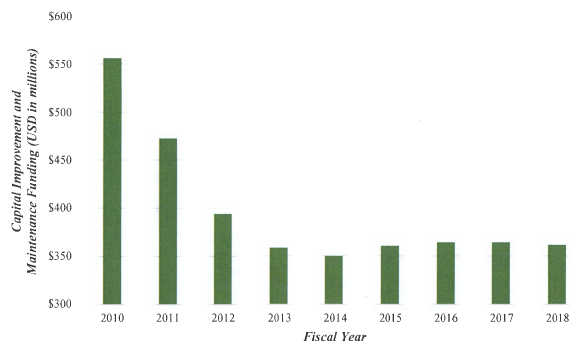

As all government agencies have, the Forest Service has an annual budget appropriated by Congress that comes from tax revenue. The part of the USFS budget we’re interested in here is the Capital Improvement and Maintenance fund, also known as the CIM budget. Between 2010 and 2014, CIM funding dropped by 37% before stabilizing after 2015.6

Appropriated CIM budget 2010 - 2018 6

Appropriated CIM budget 2010 - 2018 6

Unfortunately, the Forest Service explicitly states that this level of CIM funding only allows them to repair issues that pose an immediate health and safety risk.6 Everything else is effectively unmaintained.

Region 6 & Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest

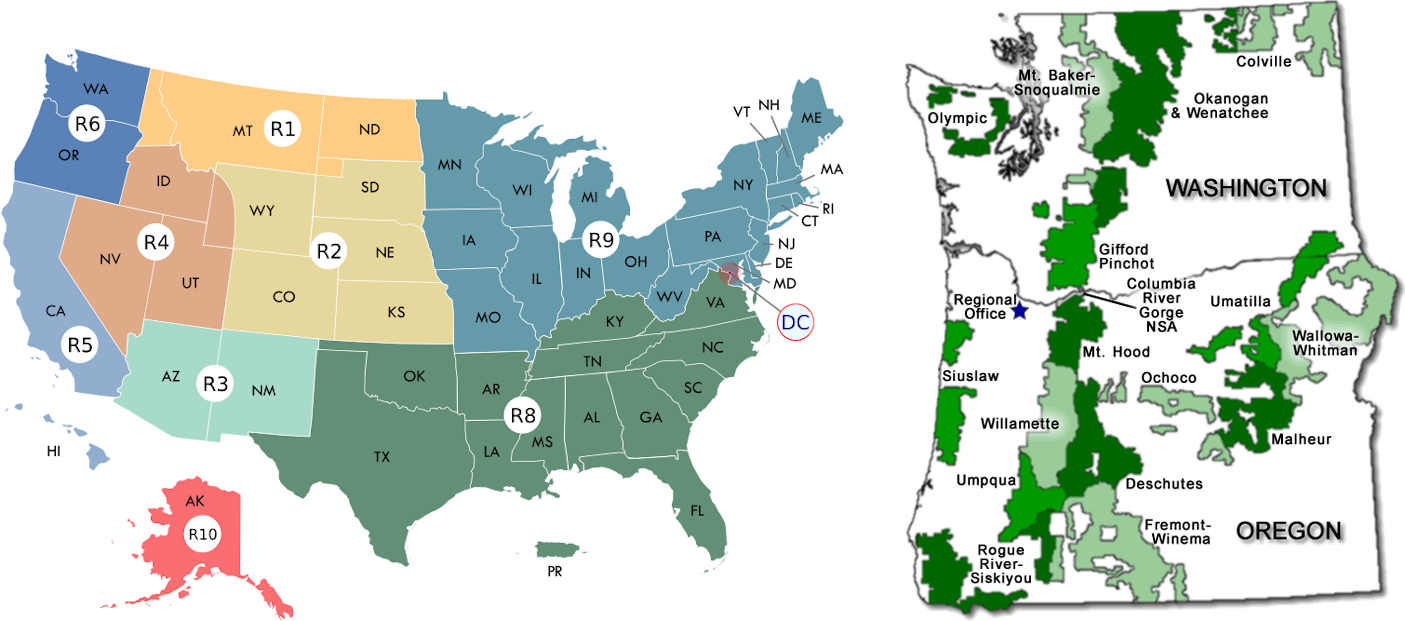

It’s here that I want to switch from looking at budgets at the national level to the regional level to better understand what’s going on at a more local and relatable level. Specifically, let’s look at the PNW forest region and the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest (MBS) as this is the region I live in and the forest that I and many of my fellow Seattle-area residents spend most of our time in.

One more housekeeping note on the organization of the Forest Service: The USFS is divided into nine regions, R1-R10 (region 7 does not exist anymore). Each region is then divided further into National Forests and each Forest is divided into Ranger Districts. Each of these units have their own budgets.

Forest Service regional organization

Forest Service regional organization

With that said, let’s take a look at the exactly how much funding is needed to maintain the roads in Region 6 (the PNW). The table below lists the deferred and annual maintenance costs for each forest in Region 6 as of 2015.

The difference between deferred and annual maintenance being:

- Deferred Maintenance: Maintenance that was not performed when it should have been or was put off or delayed for a future period. When allowed to accumulate without limits or consideration of useful life, deferred maintenance leads to deterioration of performance, increased costs to repair, and decrease in asset value.

- Annual Maintenance: Work performed to maintain serviceability or repair failures during the year in which they occur. This includes preventive and/or cyclic maintenance performed in the year in which it is scheduled to occur.7

Below is the deferred maintenance for 2015 & 2023 and annual maintenance need for 2015 (the most recent year for which I have data) for each forest in Region 6: 7 8

| National Forest | Road Miles | Annual Maintenance Need (2015) | Deferred Maintenance (2015) | Deferred Maintenance (2023) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia River Gorge | 99 | $121,557 | $1,454,584 | $454,671 |

| Colville | 4,309 | $4,306,765 | $37,336,065 | $44,657,021 |

| Deschutes | 8,109 | $7,526,877 | $80,566,681 | $29,767,043 |

| Fremont-Winema | 12,548 | $13,642,507 | $133,971,908 | $68,925,716 |

| Gifford Pinchot | 4,103 | $5,312,486 | $53,330,891 | $27,182,755 |

| Malheur | 9,628 | $6,153,833 | $56,025,932 | $24,603,985 |

| Mount Hood | 2,881 | $4,896,610 | $51,813,990 | $25,269,040 |

| Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie | 2,453 | $9,660,568 | $81,915,920 | $62,880,382 |

| Ochoco | 3,253 | $3,313,734 | $33,260,537 | $14,980,293 |

| Okanogan-Wenatchee | 8,163 | $17,050,400 | $158,111,026 | $84,572,497 |

| Olympic | 2,026 | $4,467,995 | $42,680,614 | $27,172,794 |

| Rogue River-Siskiyou | 5,288 | $11,581,995 | $111,614,953 | $72,534,097 |

| Siuslaw | 2,128 | $2,777,636 | $26,115,387 | $16,091,493 |

| Umatilla | 4,624 | $6,647,168 | $65,211,612 | $32,083,051 |

| Umpqua | 4,776 | $7,148,103 | $73,669,140 | $36,795,738 |

| Wallowa-Whitman | 9,150 | $6,808,709 | $64,279,905 | $30,869,516 |

| Willamette | 6,542 | $8,838,067 | $90,942,456 | $47,717,136 |

| Total | 90,078 | $120,255,010 | $1,162,301,600 | $646,557,228 |

The caveat here is that the source of this data notes these 2015 numbers are to return the road network to a “like new” condition. For practical purposes we don’t necessarily need “like new” conditions everywhere so an actual number may be somewhat smaller but regardless this makes for a decent ballpark upper-bound figure.

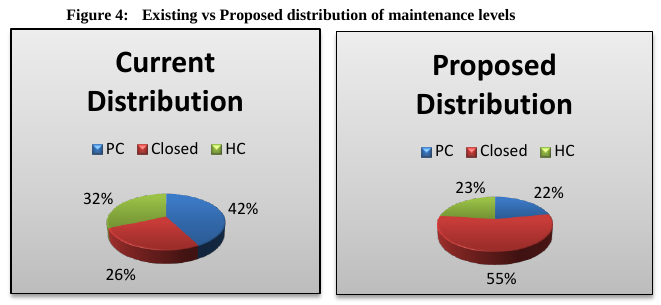

Wait a second though, the numbers above show that as of 2015 the deferred maintenance for the region was estimated at just over $1.1B7 compared to $646M in 2023. Progress on the backlog must be being made then, right? Unfortunately not. This is not because the backlog is being caught up with but rather because roads are simply being closed or downgraded in quality thus getting the deferred maintenance they incurred off the books. Consider the following proposed distribution of road maintenance levels from 2015: 7

Due to the lack of funding the percentage of closed roads was proposed to be doubled. The roads accessible to low-clearance, passenger cars (PC) reduced by a third and the roads accessible to high-clearance vehicles (HC) halved.

This is also a good time to mention that even if you are lucky enough to have a high-clearance vehicle and are happy with certain roads being harder to pass as a way of controlling crowds, this lack of maintenance funding still affects your access as formerly high-clearance-only roads degrade to the point of being impassable to any vehicle and closed entirely. It is also more expensive to rehabilitate a road that was unmaintained or under-maintained. Preventative maintenance is almost always cheaper in the long run and the obstacles to re-opening a closed road are extremely high.

As an aside, the Forest Service categorizes roads into five maintenance levels with levels 5, 4, and 3 being suitable for low-clearance, passenger vehicles, level 2 being suitable for high-clearance vehicles, and level 1 being closed to traffic.

Road maintenance levels examples, levels 5 - 1 left to right 9

Road maintenance levels examples, levels 5 - 1 left to right 9

A short term solution to addressing budget shortfalls, therefore, is to reduce the maintenance level of roads or close them outright. This reduces the deferred maintenance backlog at the expense of losing access entirely to areas served by now closed roads or reducing access to only high-clearance vehicles. Given the lack of funding this is what the Forest Service has been forced to do in recent years. Because of that, the annual maintenance need is correspondingly likely somewhat lower now from 2015 but not by an appreciable amount, especially when factoring in inflation.

In the case of Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie (MBS) specifically, ignoring the backlog of deferred maintenance, just shy of $10M/year is needed to maintain its roads.7 How much funding is the forest getting then? The average annual road maintenance budget between 2008 and 2012 was $810k.7 By 2013 that number was down to $400k.10

A clear trend starts to emerge here:

- In 1998, the Forest Service estimated they had funding to maintain 40% of the network.1

- With the collapse of timber receipts after the 1990s, at 2008-2012 funding levels that was down to 25%.10

- As noted above, by 2013 further reduced CIM funding took it down to 7% if efforts were focused on solely on a small subset of roads to maintain to standard.7

Yikes.

Wildfires

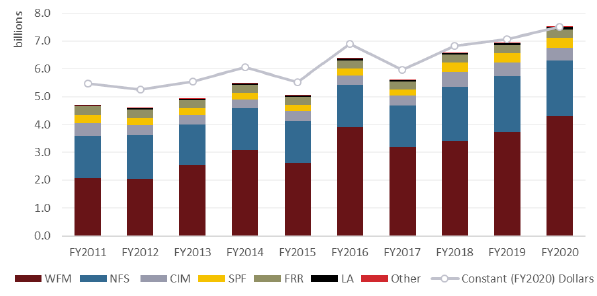

Despite all of this, it’s notable that the Forest Service’s overall national budget actually increased from $5.1B to $8.2B between 2011 and 2020.11 Even adjusted for inflation, this represents a 36% increase in funding. So what’s going on here? Why has the budget increased by so much in real dollars but the maintenance budgets keep getting slashed?

This additional funding has primarily gone to wildfire fire fighting. And even with that increase fire fighting needs have diverted funding from other programs. The wildfire account in the budgets is named “Wildland Fire Management” or WFM. In the chart below, it’s evident how much the WFM funding has increased from 2011 to 2020 while the maintenance budget (CIM) shrunk from 2011 levels (although it did noticeably grow starting in 2018 which we’ll get back to):

Forest Service Discretionary Appropriations by Account, FY2011-FY2020 11

Forest Service Discretionary Appropriations by Account, FY2011-FY2020 11

Or rather in table format: 11

| Year | CIM Budget | WFM Budget |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | $459.6M | $2.0B |

| 2012 | $382.1M | $2.0B |

| 2013 | $346.5M | $2.5B |

| 2014 | $333.0M | $3.0B |

| 2015 | $343.4M | $2.6B |

| 2016 | $348.2M | $3.9B |

| 2017 | $348.0M | $3.1B |

| 2018 | $525.6M | $3.4B |

| 2019 | $467.0M | $3.7B |

| 2020 | $466.8M | $4.3B |

While the CIM budget dipped between 2011 and 2017 before returning to 2011 levels in 2018, the WFM budget was more than doubled by 2020. Of course, this is understandable given the crisis levels of wildfires we have been dealing with over the past decade. The issue is that these emergencies have risen to the level of creating another budgetary issue: fire borrowing.

The Congressional report Forest Service Appropriations: Ten-Year Data and Trends (FY2011-FY2020) states the following regarding fire borrowing:

Overall appropriations to the FS for wildfire-related activities have increased considerably since the 1990s. A significant portion of that increase is related to rising suppression costs, even during years of relatively mild wildfire activity, although the costs vary annually and are difficult to predict.

Due to the emergency nature of fire control activities, appropriations laws provide the FS authority to transfer money out of other discretionary accounts if suppression funds become depleted; this is often referred to as fire borrowing. When such transfers have occurred, Congress typically has enacted supplemental appropriations to repay the transferred funds and/or to replenish the agency’s wildfire accounts, though sometimes these funds have been provided in subsequent fiscal years.11

In recent years efforts have been made to reduce the impact of fire borrowing on other areas of the budget, but the practice remains. Even when diverted funds are subsequently replaced this borrowing still creates unpredictability which has the potential to derail any project planning to address deferred maintenance. In the meantime, the agency has directly noted the impact of fire borrowing on the CIM budget up to this point:

Complicating the increased constraints on CIM funding, large amounts of the Agency’s funding must be allocated to fight large wildfires. Wildfire suppression operations have had a substantial impact on the Agency’s ability to financially plan, design, and implement responses to its growing portfolio of unmaintained infrastructure assets. Rising costs and fire borrowing have diverted much-needed funds away from CIM efforts, thereby increasing the delays and costs of deferred maintenance projects. As a solution, Congress enacted a wildfire cap adjustment that will virtually eliminate the need for fire borrowing starting in FY2020.6

The last statement about the wildfire cap introduced in 2020 is notable and hopefully this will therefore be less of an issue in the future, but it is still important to note fire borrowing to understand how the maintenance backlog became so large.

It’s not just budgetary effects either. In 1995, there were 18,000 staff working in the Forest Service plus another 5,700 fire personnel. By 2015 general staff decreased to 11,000 while fire personnel increased to 12,000.12 Even with funding provided for maintenance in a given year, this leaves far fewer employees to make use of that funding as all the money in the world doesn’t mean much if there’s an insufficient staff to put it to use.

Overall, in 1995 16% of the Forest Service budget was dedicated to wildfires. By 2015 it was 52% and by 2025 it’s projected to be upwards of 67%.12 Without large amounts of additional funding it is virtually guaranteed that the Forest Service’s budget will continue to be siphoned away by firefighting needs.

Recreation Passes

Now at this point you may be thinking “hang on, I pay for a Northwest Forest Pass/America The Beautiful Pass each year to use all these trails. Isn’t that paying for these trails and roads?” And that is an excellent question. These do provide a non-trivial amount of revenue, but not as much as you may think and it doesn’t necessarily go towards what you may think it does.

…you did buy a pass before parking at the trailhead, right?

The Forest Service publishes data specifically on how much revenue the Recreation Fee Program brings in and where it goes each year. For 2022 the breakdown for Region 6 and the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie Forest (MBS) was: 13 14

| Revenue | Region 6 | MBS Forest |

|---|---|---|

| Recreation Fees | $10.1M | $1.1M |

| Interagency Passes (America the Beautiful Pass) | $959k | $234k |

| Special Uses | $1.7M | $221k |

| Total | $12.8M | $1.6M |

| Expenditures | Region 6 | MBS Forest |

|---|---|---|

| Repair and Maintenance | $5M | $857k |

| Visitor Services | $2.5M | $139k |

| Law Enforcement | $109k | $50k |

| Habitat Restoration | $7k | $0 |

| Fee Agreements | $12k | $0 |

| Collections/Overhead | $917k | $71k |

| Total | $8.7M | $1.1M |

It’s hardly covering all of the needed costs, but it’s certainly not nothing! However, for MBS specifically it was shown earlier that the annual maintenance need is in the neighborhood of $10M whereas the annual appropriations budget was around $400k after 2013. So while that $857k directed towards repair & maintenance comprises a huge chunk of the overall maintenance revenue, the forest still has only around 13% of what it needs.

Additionally, it is worth noting that the Forest Service primarily uses these funds for trail maintenance rather than roads.15 Which is certainly important, but since this article is focused on forest roads it’s important to note that the revenue collected from the recreation fee programs is almost entirely dedicated to trail maintenance rather than road maintenance. And the trails are of no use if there’s no way to get to them so both trail and road maintenance are critical.

Other Funds

Despite all of this, there is a big piece of the puzzle that has been left out until this point. Annual appropriations don’t tell the whole story about funding; there are additional supplemental government permanent or temporary programs that will provide non-trivial amounts of funding for individual projects. Any analysis of forest road funding would be massively incomplete without considering them so let’s take a look at the main ones.

A note: This is not meant to be an exhaustive list of programs that provide forest road funding. Tracking down every single source of funding for the Forest Service is a task well outside the wheelhouse of my little blog. The goal here was to touch on the main/current ones to get a general idea of funding levels.

Roads and Trails Fund

Let’s start with one of the oldest funds: The Roads and Trails Fund was established in 1913 and allows for 10% of revenues generated from uses of National Forests to be used for construction and maintenance of roads and trails in the forests.11 For example, the aforementioned timber receipts.

That sounds great, except that since 1982 appropriations laws have instead directed all of these revenues to the general fund of the US Treasury instead.4 Alright, what else we got?

Legacy Roads and Trails

The appropriately named Legacy Roads and Trails program was first created in 2008 with the goal of repairing, well, roads & trails, decommissioning roads, and removing fish passage barriers. Each year this fund must be reauthorized with varying levels of funding. For example, in 2013 it was funded with $39M16 yet in 2018 it was funded with $40M.5 As in, inflation has taken a toll on funding levels here.

This fund is a fraction of what is needed, however. For instance, in 2011 this funding maintained and improved just over 1,500 miles of road across the entire network.16 Keep in mind that the forest road network is around 375,000 miles in total. So that covers 0.4% of the network. Granted, this was only a single year and, sure, it’s better than nothing, but funding to maintain under 1% of the network is hardly going to move the needle on keeping up with needed maintenance let alone catching up on deferred maintenance.

Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

In 2012, the Federal Lands Transportation Program (FLTP) was first established by the Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century Act. It provided $300M/yr in funding for transportation-related facilities on federal lands administered by the National Park Service (NPS), Fish and Wildlife Service, and Forest Service. It was reauthorized in 2015 by the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act and most recently again in 2021 by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, colloquially known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law of 2021. By 2026 FLTP will provide $456M in funding.17

That’s actually a fairly significant amount! Except… the overwhelming majority of this funding goes to the NPS. Of that $456M to be allocated in 2026, $360M will go to the NPS, $36M to the Fish and Wildlife Service, and $28M to the Forest Service.17

Of course, the NPS badly needs funding as well, but the point is that the FLTP also will not appreciably reduce the Forest Service’s deferred maintenance backlog. As noted at the start of this article, this is not an article about the NPS so the impact of this funding on their backlogs is out of scope here.

Aside from re-authorizing FLTP, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law does not provide much in the way of funding for road maintenance. It does provide $5.5B for the Forest Service to “restore ecosystems and reduce wildfire risk to communities” as well as “important tools to support agency efforts to establish resilient landscapes for future climate conditions.”18

Inflation Reduction Act

The 2022 Inflation Reduction Act provided an additional one-time $5B appropriation for additional wildfire resilience measures.18 As far as I understand, this funding is not to help with road maintenance but was worth mentioning here due to its recency and high-profile nature.

Great American Outdoors Act

Finally we arrive at the 2020 Great American Outdoors Act (GAOA). This act was the most consequential law in recent years for improving the maintenance funding situation and general access to outdoor recreation. In the most broad strokes the GAOA consists of two main components:

- It established permanent funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF). This fund existed since 1964, but lacked permanent yearly funding. GAOA established a permanent $900M/yr funded by offshore oil and gas drilling royalties (as was the case since the fund’s inception).19

- It created the Legacy Restoration Fund with $9.5B of funding over five years. This fund is targeted at addressing maintenance specifically.19

For example, since at the time of this writing it is 2024 we are already most of the way through the Legacy Restoration Fund’s life. We can therefore see some of the projects that GAOA has accomplished already. Below is a list of GAOA-funded projects for the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie forest specifically:

| Forest | Project | GAOA Non-transportation funding | GAOA transportation funding |

|---|---|---|---|

| MBS | Mountain Loop Highway Corridor Enhancement | $225k | |

| MBS | Pacific Crest Trail Access Roads, Bridges, and Trails Deferred Maintenance | $1.3M | $200k |

| MBS | Bridge Repairs and Preservation | $600k | |

| MBS | Heather Meadows Trails and Recreation Site Deferred Maintenance and Dam Rehab | $60k | |

| MBS | Mountain Loop Highway Road, Trail, and Bridges Deferred Maintenance | $450k | $1M |

See Appendix D in 18 for a full list of GAOA-funded projects in Region 6

This all sounds great, but as usual the devil is in the details so what’s the asterisk on this?

For the LWCF, its funding is split between federal use to acquire land and grants to states for projects of their choice.20 Both important uses, but not ones relevant to addressing the deferred maintenance backlog on federal lands.

As a small digression, a local example of LWCF funding used for state-specific projects, Seattle readers of this article have the LWCF to thank for part of the development of Gas Works park in years past:

LWCF funding for Gas Works Park is an investment in Seattle’s quality of life that has paid dividends. […] Without LWCF funding, the City would have been unable to develop the 2-acre northwest portion of the park, which had been inaccessible and vacant for many years.21

For the Legacy Restoration Fund, the issue is that $6.65B of the allocated $9.5B of this goes to the NPS rather than the USFS.22 The Forest Service can get at most $285M/yr or just shy of $1.5B over the lifetime of the five years of the fund. Moreover, the GAOA stipulates that 65% of each agency’s funding must be used for non-transportation projects23 (hence the distinction in the table above).

Remember that the deferred road maintenance backlog in Region 6 alone was $646M as of 2023. For simplicity assume this $1.5B is spread equally over all nine USFS regions and then take 35% of that for the allowed quota of transportation projects. That’s ~8% of the total deferred road maintenance for Region 6. Which is certainly something, but still leaves 92% of the backlog unaccounted for and is only funded for five years, which we are already one year from the end of as of this writing.

Again though, this is not to diminish the needs of the NPS over those of the USFS. So far $173M of the NPS’s share of GAOA funding has gone to multiple much needed projects in Washington.22

Budget Summary

Alright, so after analyzing all of those sources of funding, what conclusions can we draw about the state of funding for our forest roads? Overall, there are a few high level takeaways up to this point:

- The traditional source of forest road maintenance funding, timber receipts, dramatically dried up with the collapse of the logging industry in the 1990s.

- Since then, appropriations to maintain the existing roads have been further reduced leaving the Forest Service able to maintain only a small percentage of the roads.

- Meanwhile the deferred maintenance backlog has only grown forcing the Forest Service to permanently close roads or downgrade their maintenance level.

- In recent years, funding has been diverted to more pressing wildfire fighting needs.

- Recent laws aimed at addressing these maintenance backlogs of federal recreational facilities have been directed primarily at the NPS rather than the USFS.

Therefore, the unfortunate reality is that the current level of funding for our forest roads remains woefully inadequate. With this level of funding we can expect to see more roads falling further into disrepair, becoming inaccessible to most vehicles, and ultimately being closed & lost forever regardless of what vehicle you may drive.

Let’s now turn to how we can avoid this future.

Potential Mitigations

In an ideal world the annual appropriations from Congress would cover the needed annual maintenance budget plus some extra to work through the deferred maintenance backlog, but this is unrealistic to expect. The federal budget has enough strain on it already and the USFS is hardly the only agency feeling this pinch. As valuable as I honestly believe outdoor recreational access to be for the public, there are higher priorities than maintaining some roads in a forest. So let’s assume then that the USFS annual appropriations are what they are and won’t be dramatically increasing any time soon. What can be done to prevent losing these roads forever in that case?

There’s no silver bullet solution here unfortunately. In reality, a combination of approaches are needed to get funding to where it is needed. What’s more, getting funding to 100% of what’s needed is likely even more unrealistic. But that’s not an excuse to not attempt to at least improve the situation and why this section is titled “mitigations” rather then “solutions.”

Maybe instead of being able to maintain a paltry ~5% of the roads, we could maintain 50% of them. With maintenance efforts focused on the most popular roads for recreational access we would at least not be slowly losing access to trailheads entirely.

1. Extend the GAOA Legacy Restoration Fund

An easy win would be to extend the Great American Outdoors Act’s Legacy Restoration Fund (LRF) for another five years. Above it was mentioned that the GAOA established the LRF with $9.5B of funding over five years. This was in 2020 so as of this writing there is one more year left in this program. Extending it for another five year term would provide a significant amount of additional funding for working on the deferred maintenance backlog. Perhaps make it a ten year term or maybe even give it permanent funding? Given it passed the House with a 2/3 majority and the Senate with a 3/4 majority,24 it should be “easy” (by Washington standards) to get an extension passed.

The LRF’s funding is currently heavily weighted towards the NPS. Ideally, the funding would be more evenly distributed between the NPS and the USFS as well so that the USFS may have adequate funding to work through its maintenance backlog too.

2. Use the Land and Water Conservation Fund for maintenance

In addition to establishing the Legacy Restoration Fund, the GAOA also provided a permanent source of funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) to the tune of $900M/yr. The LWCF is primarily used for land acquisition, however. Some of its funding could instead be directed to deferred maintenance each year instead.

Prior to the GAOA, while the fund was authorized to collect and dispense up to $900M/yr, many years it was distributing much less.25 Rarely did appropriations exceed even $500M. With the GAOA it is now fully funded each year leaving a significant amount of money that was previously not being fully utilized by the LWCF.

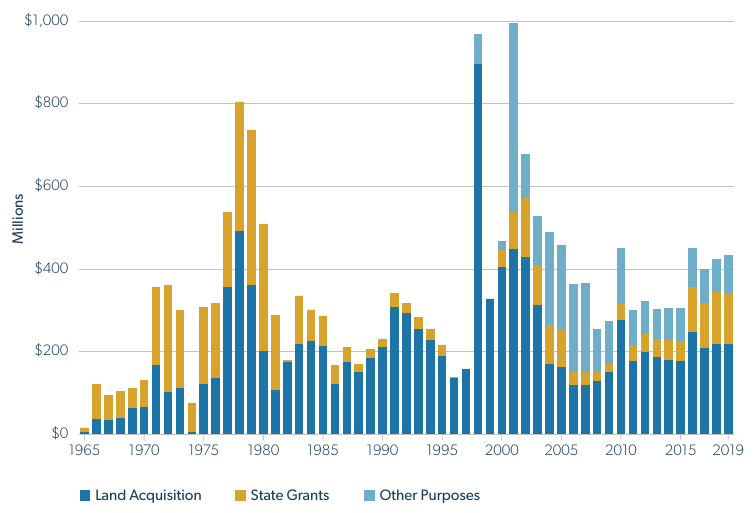

LWCF Annual Discretionary Appropriations (in millions, not inflation adjusted)25

LWCF Annual Discretionary Appropriations (in millions, not inflation adjusted)25

That’s not to say it should be entirely used for maintenance over land acquisition, but it could be argued that maintenance needs of already-owned federal lands trumps new acquisitions moreso now than when the fund was established in 1964. Needs change over time and the laws written to meet those needs should adapt as well.

Ideally the LWCF’s funding would be pegged to inflation too to ensure it does not become further eroded in the future now that it is fully funded.

3. Increase enforcement of recreation passes

As discussed above, revenue from recreation passes (Northwest Forest Pass, America the Beautiful Pass) for Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest in 2022 was $1.6M.14 Now this is anecdotal, but it seems that at most trailheads only around half of vehicles have a pass displayed on them. At the more popular trails this number can be even lower, or some people mistakenly believe that Washington’s Discover Pass is valid on federal land. Moreover, in all my years hiking the Cascades I have seen the Forest Service enforcing recreation passes at a trailhead a single time.

Given that recreation passes contributed $1.6M in funding already, increased enforcement of these passes represents an opportunity to increase funding significantly simply by enforcing laws already on the books. Yes, enforcement itself costs money and getting to 100% is unrealistic, but as it stands nearly no enforcement at all leads many to forgo passes as it’s known the chances of getting caught without one are so low. A small amount of increased enforcement (and fines for those without passes) has the ability to collect a non-trivial amount of additional funding that could be used for maintenance of these facilities.

4. Raise the cost of recreation passes

This option is a difficult one to propose. First and foremost, the objective is not to price anyone out, which I’ll address in just a moment. Here’s the thing though: the cost of a Northwest Forest Pass (NWFP) and interagency (America The Beautiful) pass are simply too low.

Consider the NWFP: When it was introduced in 1997 a yearly pass cost $25. Today it is $30/yr. If the cost of the pass was simply kept consistent with inflation it would be $49/yr. Remember that the recreation fees brought in $10M in revenue for Region 6 in 2022 13 and that the annual road maintenance in 2015 was $120M/yr. Adjusting the cost for inflation would yield an additional ~$6.5M in revenue. Not that this alone is going to solve the problem, but it’s a non-trivial amount of funding and only keeps the cost consistent with what it was historically.

Now consider the timeframe the NWFP was first introduced. This was in the mid-1990s, a time when the logging industry had only just started to retreat taking much of the timber receipt funding with it. The maintenance backlog was less and the funding situation for annual maintenance was much less dire. $25/yr may have been reasonable back then. The fiscal environment is entirely different now. As much as we would all love for the government to fund maintenance or for some resource extraction industry to pay for it, the reality of the situation is that roads cost money and that money has to come from somewhere. If other sources of funding are not forthcoming it would fall on the users of these roads to pay for them lest we allow them to go unmaintained and accept they will disappear. Assuming that’s not the conclusion, it would be reasonable to accept increased fees to pay for these roads. Thus, realistically the cost of recreational passes should be considerably higher to 1. adjust them for inflation, and 2. pay for at least some of the annual maintenance needs to help supplement other revenue sources. Exactly what that number should be is outside of scope here, but the point is that the current fees are simply much too low.

This is absolutely not to say that we should purposefully be gatekeeping low income people out of the forests. There are few options here: Have a cheaper rate for those below a certain income threshold, make a certain number of passes available for checkout at local libraries, or offer free passes to volunteers that do trail work or trash pickups (as the NPS already does).

5. Strengthen the Roads and Trails Fund Act

The Roads and Trails Fund, mentioned earlier in this article, was established in 1913 to provide funding for construction and maintenance of roads and trails in national forests. Specifically 10% of all revenue generated from forest products would be directed back to the forest’s roads and trails.26 While this funding is permanent, unfortunately, the phrasing of this act is fairly weak and does not strictly require that 10% of funds be directed back to the forests but rather “may whenever practical” be directed back to the forests. As such, since 1982, this funding was sent to the general fund of the Treasury to offset annual appropriations for road/trail maintenance.4

During my research for this article I found one reference to the 2020 President’s Budget proposing that the revenue collected by the Roads and Trails Fund once again be used for its intended purpose.6 It is not clear if this was enacted, however, as I could not locate any further information on if this proposal was enacted. Regardless, a better long term solution would be to reform the 1913 act to mandate that revenue collected is used for road and trail maintenance rather than only “whenever practical.”

6. Make use of the Highway Trust Fund

In 1956 the Federal Aid Highway Act created the Highway Trust Fund to finance interstate highway (and other road) construction and maintenance. It is funded by a 18.5 cent per gallon tax on gasoline. Since forest roads are federal roads on federal land and the Highway Trust Fund is presently used not only for interstate highways but also surface roads and the gas used to travel on these roads is subject to the federal gas tax it would not be unreasonable to provide funding to maintain them from the Highway Trust Fund too. Considering the federal gas tax revenue was over $50B in 202327 and the road maintenance needs for Forest Service Region 6 were $120M in 20157, this is a fairly small amount.

There is a caveat to this one though. The federal gas tax is already insufficient to fund the Highway Trust Fund. Between inflation, increased fuel efficiency of cars, and electric vehicles, the revenue going towards the Highway Trust Fund has been declining. The federal gas tax itself has not been raised since 1993 despite inflation halving the value it collects in real dollars since then. In fact, since 2008 over $275B in general tax revenue has been transferred to to the Highway Trust Fund to keep it solvent.28 As gasoline use declines a new solution will need to be found for road funding. The federal gas tax also needs to be raised to at least be consistent with inflation. Anything that makes gas more expensive is a political lightning rod, but if you don’t pay taxes for roads at the gas pump, general tax funds are used instead. Either way you are being taxed to pay for roads; nothing is free and roads are no exception. The pending insolvency of highway funding is a separate topic entirely, however.

7. Allow more concessionaires

For reference, a concessionaire is a private business that has a contract with the USFS or NPS to provide services or operate facilities in a forest or park. For instance, many of the sightseeing tours, retail/lodging operations, food services, etc. in our National Parks are operated by private concessionaires rather than the NPS directly.

How does this help with road maintenance then? Commercial operations have direct lines of revenue and are only able to operate with acceptable levels of infrastructure to their area of operation. This means it is essential to maintain the areas they operate in. For example, consider Cascade Powder Guides. They are a cat skiing company that operates near Stevens Pass on USFS land. Access is through forest road 6710 and their revenue is what pays for winter plowing of (a portion of) that road. No matter what happens, as long as they are in operation, that road will remain well maintained.

More concessionaires would mean more businesses with strong interests in maintaining access to their respective areas of operations. Perhaps small lodges could be built at certain trailheads. This would be useful for road maintenance of course, but also with providing more options for people to enjoy the mountains.

To be clear, there is a balance here. This is not a proposal to start building massive luxury hotels along every forest road. Rather it is a proposal to allow some well-balanced development in areas where it is already legally feasible (as in, not wilderness areas) as a source of revenue for forest management and recreation. I understand that this is a fine line to walk, but keep in mind that if this line was not walked in the past we would not have our National Parks as they exist today as they are a tradeoff between development/recreational access and preservation.

Take the Sperry Chalet in Glacier National Park for example. The chalet is a backcountry hotel (meaning it is hike-in only) located within the park originally built in 1914 by the Great Northern Railway. With only 17 rooms, the chalet is a small operation that does not drive disproportionate amounts of traffic to its area of the park. It also serves as a example for how modern construction can remain true to historic construction methods as the hotel was faithfully rebuilt following a 2017 fire that destroyed the building.

There are many options here and what makes sense in one area may not make sense in another. But consider that in addition to providing revenue for maintaining a certain area, concessionaires provide access to the mountains for people that otherwise may not be able to access areas to due physical limitations. In the example of the Sperry Chalet, access via horse is possible for those physically unable to make the 3,000+ vertical feet hike to the chalet. It’s important to keep in mind that access to our mountains is for more than only those capable of hiking thousands of vertical feet with a 40lbs backpacking pack on.

8. Increase sustainable logging

Taken at face value suggesting to increase logging would seem like an absurd proposal. However, there is a compelling case to make for increased logging.

As shown at the start of this article, the amount of logging done today is a fraction of what it historically was. That’s not to say it would be wise to return to peak levels of logging we once saw, but rather that the current levels of logging are at historic lows and it is possible to increase logging while still being sustainable. The main benefits to this are:

- Timber receipts were directly responsible for the initial build-out of the forest road network. Increased logging would once again fund road maintenance.

- Surprisingly enough, carbon sequestration rates are higher on private, managed forests than in public forests despite these private forests having higher levels of logging.29 Increased sustainable logging on public lands is not a forgone environmental catastrophe as many would make it out to be.

- Modern sustainable logging techniques, not clear cutting entire areas, thins forests reducing their susceptibility to massively damaging wildfires.

- Many areas that were harvested in decades past are ready for second or even third harvests. To be abundantly clear, this is not a proposal to start clearing never logged, old growth forests again.

- After all, many of these roads were originally built for logging access. By definition, they lead to areas that were already logged. So logging them again is not cutting pristine forest land. And the areas beyond the roads are generally highly protected wilderness areas where logging is completely prohibited; that does not change.

In fact, this is already happening. In 2018, 3.1 billion board feet of timber was harvested. This is the highest level since 1999,6 but still far shy of the peak levels of ~12B board feet. We are learning how to log more sustainably than in decades past and that is an unequivocally good thing.

Mt. Pilchuck case study

To illustrate this proposal with a concrete example, let’s take a look at the Mt. Pilchuck road as an example of how logging helps improve recreation access. The road to the Mt. Pilchuck trailhead was originally built as a, you guessed it, logging road in the 1950s. Its terminus then served as the parking lot and base area for the Pilchuck ski area until its closure in 1978 (in fact, I’ve previously written about the feasibility of re-establishing winter access to Pilchuck noting that the main roadblock was the poor state of the road). Since then, the Mt. Pilchuck trail and the lower elevation Heather Lake trail have become two of the most popular hikes along the Mountain Loop Highway corridor. The problem was that prior to 2024, the Mt. Pilchuck road had become the poster child for poorly maintained forest roads in that corridor. It was so bad that news articles were written about it.

But then in 2023 the road was closed for the entire summer while it was fully repaired with the Heather Lake trailhead parking tripled in size. When it reopened for the 2024 season the road had been transformed into one of the best forest roads your esteemed author has ever driven on.

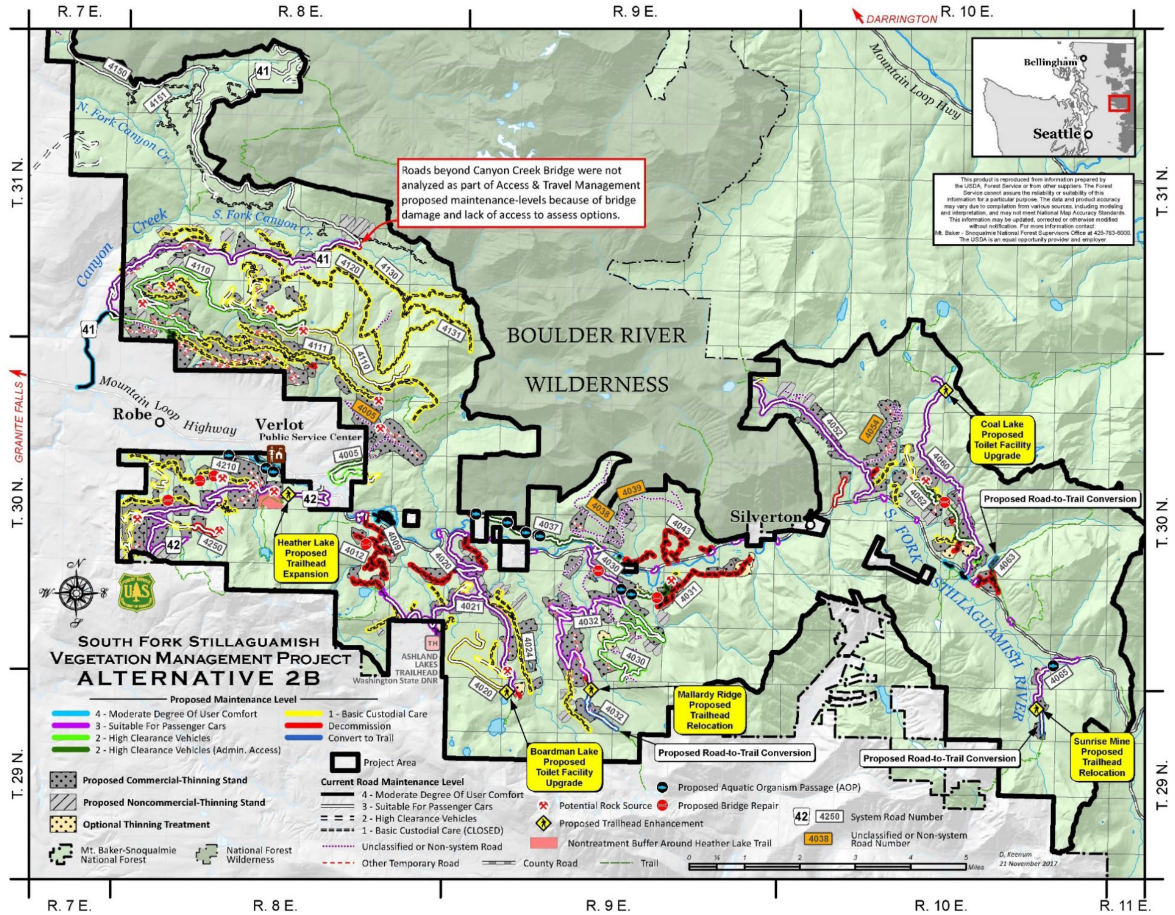

What happened to accomplish this? Well, the road was not repaired because of annual maintenance funding or any other federal funding source. Rather, it was part of the South Fork Stillaguamish Vegetation Management Project. This project encompassed an area much larger than just along the Pilchuck road.

As can be seen from the map above, this logging project is directly responsible for road/bridge repairs and trailhead upgrades all along the Granite Falls side of Mountain Loop Highway.

It was not without its share of controversy and legal battles, however. In 2020 the North Cascades Conservation Council filed a lawsuit against the USFS arguing, among other items, that the proposed logging was too heavy, the NEPA (environmental) review was inadequate, and that there would be a net positive amount of roads constructed going against the 1994 Northwest Forest Plan30 (the 1994 plan directs projects to have an overall net reduction or at least neutral impact on the size of the forest road network).

There’s a lot to unpack with this case that would be off-topic for this article. The short of it is that the USFS noted the need for thinning of these areas due to maintain forest health by:

Thin[ning] previously harvested stands that are currently 20 to 80 year second growth stands of age within the SF of the Stillaguamish River drainage. The goals of the stand treatments are to promote old forest characteristics with large diameter trees, stands with multiple layers of canopy, and the retention of down wood and snag components. The proposed thinning also has the goals of enhancing species diversity, maintaining a high rate of growth on dominant trees, developing desired vegetation stocking and diversity in Riparian Reserves, and promoting desired growth and stand conditions across the landscape for resiliency to climate change.31

As for the inadequate NEPA review, all of the documentation for the NEPA review is publicly available. You can be the judge of if it was inadequate or not. I’ve previously written about the weaponization of NEPA reviews by special interest groups that simply want to throw up roadblocks to any and all projects (NIMBYs in other words). This is unfortunately another classic example of that having served no purpose other than to waste time and money that could have been used for additional forest management projects.

Here in 2024 the project is thankfully well underway despite a 2022 appeal. There is already a freshly repaired Pilchuck road to show for it and an expanded Heather Lake trailhead. And that is only along one of the roads involved in the project. This area now has an ongoing source of maintenance funding, better road drainage protecting downstream water resources, improved recreational access/facilities, lower wildfire risk, a healthier forest that more closely resembles the old growth forest before logging began in the 1940s, and the economic benefits of the jobs provided by the mills in Darrington. It’s a win-win all around.

Imagine applying that same playbook to other areas in need of road, trail, and forest maintenance.

Conclusions

The harsh reality here is that this topic does not have a happy ending. The current maintenance funding of the forest road network is woefully and borderline hopelessly inadequate. The high level summary of this article being:

- The forest road network was built during the heyday of the logging industry and funded primarily through timber receipts.

- With logging now back to pre-1950s levels, the traditional source of funding for road maintenance has largely dried up.

- The current funding is only able to maintain 7% of the roads.

- This has left us with a massive deferred maintenance backlog and an annual maintenance budget that is only sufficient to maintain a fraction of the road network.

- Due to this budget shortfall the forest service has been forced to downgrade roads’ maintenance levels or close them entirely.

- Despite all of that, there are many possible mitigations to generate additional funding to maintain at least a larger percentage of our roads if not all of them.

So, if you’re wondering why that one road to the hike you want to do is seemingly taking forever to be repaired, this is why.

To bring this full circle, this article started with an example of the Canyon Creek bridge washout (pictured right). Despite the bridge itself being in good shape, 13 years of neglect has made it susceptible to collapse due to erosion under its north abutment. The current path we are on ends with either its removal or collapse and the permanent loss of the road beyond it and potentially the trail entirely if it is deemed too dangerous to ford the river without a bridge. I imagine a world where access to the road beyond the bridge is restored via a combination of, say, sustainable logging, perhaps a small commercial lodge further up the road, or any number of other creative means of funding. The possibilities are there.

At these present levels of funding we can expect access to trails that thousands of hikers, backpackers, mountaineers, climbers, ski tourers, and more regularly utilize to slowly become less accessible before becoming lost entirely. In many ways, our mountains were more expansive and accessible in decades past. Today we have fewer options than predecessors did and when outdoor recreation was less popular. With an ever growing Washington population, this loss of access will have the side effect of forcing more recreationalists into a smaller collection of trailheads further exacerbating the overcrowding issues our mountains already experience. At a time when we should be looking at increased dispersion to alleviate this concern the exact opposite is happening.

With all of that in mind, none of this should be seen as an insurmountable problem, however. It is one that can solved with a sufficient amount of political will for making the necessary reforms to provide funding. There are many avenues for providing sufficient or at least improved maintenance funding. We need only advocate for a figurative and literal road forward.

Sources

-

Mile By Mile - Ten Years of Legacy Roads and Trails Success ↩

-

Distribution of Timber Sales Receipts Fiscal Years 1992-94 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest - Forest-wide Sustainable Roads Report ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8

-

Forest Service Appropriations: Ten-Year Data and Trends (FY2011-FY2020) ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5

-

The Rising Cost of Fire Operations: Effects on the Forest Service’s Non-Fire Work ↩ ↩2

-

Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest Recreation Fee Program Accomplishment Highlights 2022 (1) ↩ ↩2

-

Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest Recreation Fee Program Accomplishment Highlights 2022 (2) ↩ ↩2

-

Legacy Roads and Trails Program Frequently Asked Questions ↩ ↩2

-

Federal Lands Transportation Program (FLTP) - Fact Sheets ↩ ↩2

-

Fiscal Year 2023 Program Direction Pacific Northwest Region 6 ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Land and Water Conservation Fund Giving Back to You and Your Community ↩

-

Great American Outdoors Act Legacy Restoration Fund - Washington ↩ ↩2

-

Deferred Maintenance of Federal Land Management Agencies: FY2013-FY2022 Estimates and Issues ↩

-

Addressing the Maintenance Backlog on Federal Public Lands ↩ ↩2

-

Testimony on The Status of the Highway Trust Fund: 2023 Update ↩