Normally when you encounter a bug with Ruby, or any other interpreted language for that matter, using the language’s provided debugging tools are all you need to diagnose the problem and find a solution. Indeed that works 99% of the time. But what about when it doesn’t? What about when your program is so hosed that the typical debugging tooling doesn’t yield any fruitful information?

This was the situation I found myself in recently while debugging a low-level bug with Ruby. I didn’t know it when I started, but the problem lie down in glibc and all the Ruby-land debugging tools in the world would not help me. So what’s one to do? Well, if you’re running the C implementation of Ruby, MRI, then it’s GDB to the rescue. However, figuring out how to access the data needed through GDB presents a host of new challenges. Armed with the proper knowledge though and it becomes entirely feasible to debug a Ruby program through GDB which is what this post aims to explore.

But why would you want to do this?

That’s a good question. In all honesty and as far as I know, there’s very few true use cases for doing this outside of development on Ruby itself, academic curiosity, and the poor souls facing a low level bug that’s seemingly impossible to debug otherwise.

In my situation I was working with a Ruby process that would deadlock while exiting in a glibc function in rare cases. I did not have the ability to debug the Ruby process directly as it was completely unresponsive due to control being outside of Ruby when it deadlocked. The only option I had was to attach GDB to the running process in order to get visibility into the process. As I’ll get into later, this provided enough information to put the pieces of the puzzle together and solve my issue at hand. Hopefully this is not what brought you here, but if so, knowing how to debug Ruby via GDB can be a powerful tool in your toolbelt for cracking difficult low-level bugs.

GDB Basics

As someone that primarily works with Ruby and other high level languages, prior to my aforementioned boggle it had been more than a handful of years since I needed to debug anything with GDB. You may be in a similar boat so let’s start with covering enough of the basics to follow along with the rest of this post. If you’re adept with GDB already you can likely skip to the next section.

GDB is, of course, a debugger, and an extremely powerful one at that. We need only know the absolute basics here though. Let’s say we have the following C program:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

#include <stdio.h>

const char* GREETING = "Hello, world!";

void print_greeting(const char* greeting);

int main(void) {

print_greeting(GREETING);

}

void print_greeting(const char* greeting) {

puts(greeting);

}

When compiling, ensure that -ggdb is specified to create debugging symbols. It’s still possible to debug a binary without these, but it is more difficult and requires referencing the source code more. Make your life easy and add them.

1

$ gcc -ggdb hello_gdb.c

We can then debug the print_greeting function with GDB by setting a breakpoint and executing the program as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

$ gdb a.out

Reading symbols from a.out...

(gdb) break print_greeting

Breakpoint 1 at 0x115f: file hello_gdb.c, line 11.

(gdb) run

Starting program: a.out

Breakpoint 1, print_greeting (greeting=0x555555556004 "Hello, world!") at hello_gdb.c:11

11 puts(greeting);

Printing a backtrace is accomplished with where:

1

2

3

(gdb) where

#0 print_greeting (greeting=0x555555556004 "Hello, world!") at hello_gdb.c:11

#1 0x000055555555514c in main () at hello_gdb.c:7

The other notable action is assigning variables and executing functions. For example, let’s say we wanted to print out the value of a global variable or call another function through GDB:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

$ gdb a.out

Reading symbols from a.out...

(gdb) break main

Breakpoint 1 at 0x113d: file hello_gdb.c, line 7.

(gdb) run

Starting program: a.out

Breakpoint 1, main () at hello_gdb.c:7

7 print_greeting(GREETING);

(gdb) call GREETING

$1 = 0x2004 "Hello, world!"

# `p` also works for printing values

(gdb) p GREETING

$2 = 0x2004 "Hello, world!"

# Manually call the `print_greeting` function

(gdb) call print_greeting(GREETING)

Hello, world!

# Call `print_greeting` with a different argument

(gdb) call print_greeting("Hello, GDB!")

Hello, GDB!

The output above demonstrates how call can be used to print the value of variables (or more accurately, memory locations such as the global variable GREETING). It can also, ahem, call functions directly and we can pass whatever arguments we want to them such as a new string rather than the GREETING string as defined in the source code of the program. Later on we’ll use this functionality extensively to peer inside of a running Ruby process.

That should about do it for a GDB crash course. Let’s get into the meat of exploring Ruby through GDB now.

Getting a Ruby Backtrace

First things first, how can we use GDB on a Ruby process to see what our program is doing? In other words, how do we get a Ruby backtrace out of GDB?

To start, say we have the following simple Ruby program that sleeps for a while:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

def foo

puts 'Sleeping...'

sleep 1000

end

foo

Using GDB it’s trivial to get a native backtrace as such:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

$ gdb --args ruby sleep.rb

(gdb) run

Starting program: ruby sleep.rb

(gdb) where

#0 0x00007ffff763446c in ppoll () from /usr/lib/libc.so.6

#1 0x00007ffff7af471a in rb_sigwait_sleep (th=th@entry=0x55555555d040, sigwait_fd=sigwait_fd@entry=3, rel=rel@entry=0x7fffffffb9a0)

#2 0x00007ffff7af58b8 in native_sleep (th=<optimized out>, rel=0x7fffffffb9a0)

#3 0x00007ffff7af8c39 in sleep_hrtime (fl=2, rel=<optimized out>, th=0x55555555d040) at thread.c:1325

#4 rb_thread_wait_for (time=...) at thread.c:1408

#5 0x00007ffff7a4995b in rb_f_sleep (argc=1, argv=0x7ffff7430088, _=<optimized out>) at process.c:5219

#6 0x00007ffff7b31ae7 in vm_call_cfunc_with_frame (ec=0x55555555e1c0, reg_cfp=0x7ffff752ff10, calling=<optimized out>)

#7 0x00007ffff7b419c1 in vm_sendish (method_explorer=<optimized out>, block_handler=<optimized out>, cd=<optimized out>, reg_cfp=<optimized out>, ec=<optimized out>)

#8 vm_exec_core (ec=0x7fffffffb8e8, ec@entry=0x55555555e1c0, initial=1, initial@entry=0)

#9 0x00007ffff7b474e3 in rb_vm_exec (ec=0x55555555e1c0, jit_enable_p=jit_enable_p@entry=true) at vm.c:2374

#10 0x00007ffff7b488c8 in rb_iseq_eval_main (iseq=<optimized out>) at vm.c:2633

#11 0x00007ffff7957e75 in rb_ec_exec_node (ec=ec@entry=0x55555555e1c0, n=n@entry=0x7ffff7fbda48) at eval.c:289

#12 0x00007ffff795e4db in ruby_run_node (n=0x7ffff7fbda48) at eval.c:330

#13 0x0000555555555102 in rb_main (argv=0x7fffffffbf18, argc=2) at ./main.c:38

#14 main (argc=<optimized out>, argv=<optimized out>) at ./main.c:57

But that’s not especially helpful in telling us where our Ruby program is hanging. How do we use GDB to get a Ruby backtrace? Ruby actually makes this quite simple, just call rb_backtrace.

1

2

3

4

(gdb) call rb_backtrace()

from sleep.rb:8:in `<main>'

from sleep.rb:5:in `foo'

from sleep.rb:5:in `sleep'

That was easy! This will print the current backtrace to stderr. Done, right? Well, yeah, possibly actually. If you’re just looking to run a Ruby program and get a backtrace at some point during its execution then this should do you fine for the most part. But if that were the case you could also likely set a breakpoint with a Ruby debugger and get the same info with less hassle. What if you have an already running process that’s hung somewhere that you want to get a backtrace for it? That’s a more interesting situation.

In the above example, the rb_backtrace method will print to stderr of the Ruby process, not the GDB process. To demonstrate this, let’s run our Ruby process in one shell and then attach GDB to it from another:

Shell 1:

1

2

$ ./sleep.rb

Sleeping...

Shell 2:

1

2

3

$ sudo gdb -p `pgrep -n ruby`

(gdb) call rb_backtrace()

(gdb)

Back in shell 1:

1

2

3

4

5

$ ./sleep.rb

Sleeping...

from ./sleep.rb:8:in `<main>'

from ./sleep.rb:5:in `foo'

from ./sleep.rb:5:in `sleep'

What happened here? stderr is pointed at shell 1, so when we call rb_backtrace() from shell 2, the backtrace is printed out in shell 1. That’s fine for a simple example like this, but if you have an already running Ruby process you need to debug then it’s probably running as a service so stderr isn’t pointed at your terminal. Maybe it and stdout are going to a log somewhere, but let’s assume we don’t have access to them at all. How do we get our backtrace?

To solve this we need to do some more work with GDB before calling for the backtrace. Using GDB we can re-open stderr for the Ruby process to a temporary file, get our backtrace, and then reset them.

Shell 1:

1

2

$ ./sleep.rb

Sleeping...

Shell 2:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

$ sudo gdb -p `pgrep -n ruby`

(gdb) set $old_stderr = (int) dup(2)

(gdb) set $fd = (int) creat("/tmp/backtrace.txt", 0644)

(gdb) call (int) dup2($fd, 2)

(gdb) call rb_backtrace()

(gdb) call (int) dup2($old_stderr, 2)

(gdb) call (void) close($old_stderr)

(gdb) call (void) close($fd)

(gdb) quit

$ cat /tmp/backtrace.txt

from ./sleep.rb:8:in `<main>'

from ./sleep.rb:5:in `foo'

from ./sleep.rb:5:in `sleep'

What we did above was set the stderr file descriptor for the Ruby process to a file located under /tmp, called rb_backtrace() to write the backtrace to that file, and then reset stderr to its original file descriptor. This way we can see what our Ruby process is currently doing even if we don’t have access to its stderr stream and without needing to stop the already-running process.

What about other threads?

This is good and all for these simple examples, but most Ruby programs of any complexity will have multiple threads. And if you’re resorting to debugging your program like this then it’s most likely debugging a difficult to reproduce deadlock situation. rb_backtrace() will only print the backtrace of the current thread so how do we get the backtrace of all threads?

To explore this, let’s use a new example Ruby program that starts two threads which deadlock:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

#!/usr/bin/env ruby

mutex1 = Mutex.new

mutex2 = Mutex.new

thread1 = Thread.new do

mutex1.lock

sleep(1) until mutex2.locked?

mutex2.lock

end

thread2 = Thread.new do

mutex2.lock

sleep(1) until mutex1.locked?

mutex1.lock

end

# Start a third thread just so Ruby doesn't recognize the process as deadlocked and kill it before we can debug it

Thread.new {sleep(1000)}

thread1.join

thread2.join

From within GDB again, we can now print all of the running threads with info threads, switch to another thread, and print its backtrace as such:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

$ ruby deadlock.rb

# In another shell:

$ sudo gdb -p `pgrep -n ruby`

(gdb) info threads

Id Target Id Frame

* 1 Thread 0x7ff76b4637c0 (LWP 1993106) "ruby" 0x00007ff76ab5c4c6 in ppoll () from /usr/lib/libc.so.6

2 Thread 0x7ff765f3f6c0 (LWP 1993116) "deadlocked.rb:6" 0x00007ff76aae24ae in ?? () from /usr/lib/libc.so.6

3 Thread 0x7ff765d3e6c0 (LWP 1993117) "deadlocked.rb:*" 0x00007ff76aae24ae in ?? () from /usr/lib/libc.so.6

4 Thread 0x7ff765b3d6c0 (LWP 1993118) "deadlocked.rb:*" 0x00007ff76aae24ae in ?? () from /usr/lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) thread 2

[Switching to thread 2 (Thread 0x7ff765f3f6c0 (LWP 1993116))]

#0 0x00007ff76aae24ae in ?? () from /usr/lib/libc.so.6

(gdb) call rb_backtrace()

# In the first shell:

from ./deadlocked.rb:9:in `block in <main>'

from ./deadlocked.rb:9:in `lock'

Now we can see how the second thread is waiting to acquire the lock for mutex2 at line 9, which, of course, it will never get but it does pinpoint where the program is becoming stuck.

This is a bit tedious to do for every thread though, especially if you have more than just two. It’s fairly easy to automate this process to get a backtrace for every thread, however. Let’s modify the stderr redirection from above and write it to a GDB script named backtrace.gdb this time.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

set $old_stdout = (int) dup(1)

set $fd = (int) creat("/tmp/backtrace.txt", 0644)

call (int) dup2($fd, 1)

set $thread_list = rb_thread_list()

set $num_threads = rb_num2long(rb_ary_length(rb_thread_list()))

set $i = 0

while $i < $num_threads

call rb_p(rb_thread_backtrace_m(0, 0, rb_ary_entry($thread_list, $i++)))

end

call (int) dup2($old_stdout, 1)

call (void) close($old_stdout)

call (void) close($fd)

The changes to this script below are two fold:

- Redirect

stdoutrather thanstderrsince we’ll be callingrb_p(Ruby’s print function) which prints tostdoutnow. - Get every thread with

rb_thread_listand for each thread callrb_thread_backtrace_mto print a backtrace for that thread in particular.

Running it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

$ sudo gdb -p `pgrep -n ruby` -x backtrace.gdb

(gdb) quit

$ cat /tmp/backtrace.txt

["./deadlocked.rb:21:in `join'", "./deadlocked.rb:21:in `<main>'"]

["./deadlocked.rb:9:in `lock'", "./deadlocked.rb:9:in `block in <main>'"]

["./deadlocked.rb:15:in `lock'", "./deadlocked.rb:15:in `block in <main>'"]

["./deadlocked.rb:19:in `sleep'", "./deadlocked.rb:19:in `block in <main>'"]

Great! We can see above how each thread has a backtrace printed out in an array format and exactly where each of them are hung.

Into the VM

Everything above should be sufficient for all practical purposes. But if you’ve come this far you may be interested in exploring the Ruby VM a bit more while we’re in here. For instance, those backtraces, how does Ruby track what it’s currently executing in order to generate a backtrace and how can we peek into those data structures of a running process ourselves?

It’s worth nothing everything beyond this point is not necessarily practical per se; it’s primarily academic but still quite interesting to those curious about Ruby internals. Everything below targets Ruby 3.2.2 as well (the current version of MRI at the time of this writing).

There are various blog posts from prior to circa 2017 that demonstrate how to get reach into Ruby’s internal data structures by use of a global variable named ruby_current_thread. However, evidently this was removed in Ruby 2.5.0. Instead, from Ruby 2.5.0 to at least 3.2.2 (at the time of this writing), ruby_current_ec is the new variable to use for this purpose.

What is ec though? ec stands for execution_context and holds the data related to whatever Ruby is executing at a given point in time. This includes the call stack, control frame pointer, thread pointer, fiber pointer, and more. The rb_execution_context_struct definition has the full list of fields, but the short of it is that everything we’re interested in is located in this data structure either directly or through a pointer to another data structure.

Let’s take a look at what this looks like for the sleep.rb script from above (protip: use set print pretty on in GDB for easier to read outputs here):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

(gdb) call ruby_current_ec

$1 = (struct rb_execution_context_struct *) 0x5571d51461c0

# `ruby_current_ec` is a pointer so in order to print the data it points to we need to tell GDB to dereference the pointer with the dereference operator

(gdb) call *ruby_current_ec

$2 = {

vm_stack = 0x7f2316230010,

vm_stack_size = 131072,

cfp = 0x7f231632fed0,

tag = 0x7ffd5b32c250,

interrupt_flag = 0,

interrupt_mask = 0,

fiber_ptr = 0x5571d5146170,

thread_ptr = 0x5571d5145040,

local_storage = 0x0,

local_storage_recursive_hash = 139788682901840,

local_storage_recursive_hash_for_trace = 4,

storage = 4,

root_lep = 0x0,

root_svar = 0,

ensure_list = 0x0,

trace_arg = 0x0,

errinfo = 4,

passed_block_handler = 0,

raised_flag = 0 '\000',

method_missing_reason = MISSING_NOENTRY,

private_const_reference = 0,

machine = {

stack_start = 0x7ffd5b32d000,

stack_end = 0x7ffd5b32bf50,

stack_maxsize = 8372224,

regs = {

{

__jmpbuf = {93947394543840, -6100235198789993538, 0, 93947394543680, 93947394547664, 139788684347000, -122019239599424578, -3910558443652162},

__mask_was_saved = 0,

__saved_mask = {

__val = {0 <repeats 16 times>}

}

}

}

}

}

It’s best to compare the struct definition against what GDB prints out to get a better idea of what these fields are exactly. But even still, the above doesn’t tell us a whole lot about what our program is doing. In order to determine that we’ll need to explore some of the pointers to other data structures.

In particular, the control frame pointer, cfp, gives us access to what Ruby is executing in this thread. A control frame in Ruby is the data structure that the VM uses to track both your program’s stack and it’s own internal stack in YARV. YARV itself is an entirely different topic that’s outside the scope of this post, but in short it’s the internal bytecode interpreter for Ruby. It has its own internal stack for managing the execution of bytecode instructions. A control frame holds pointers to both of these stacks.

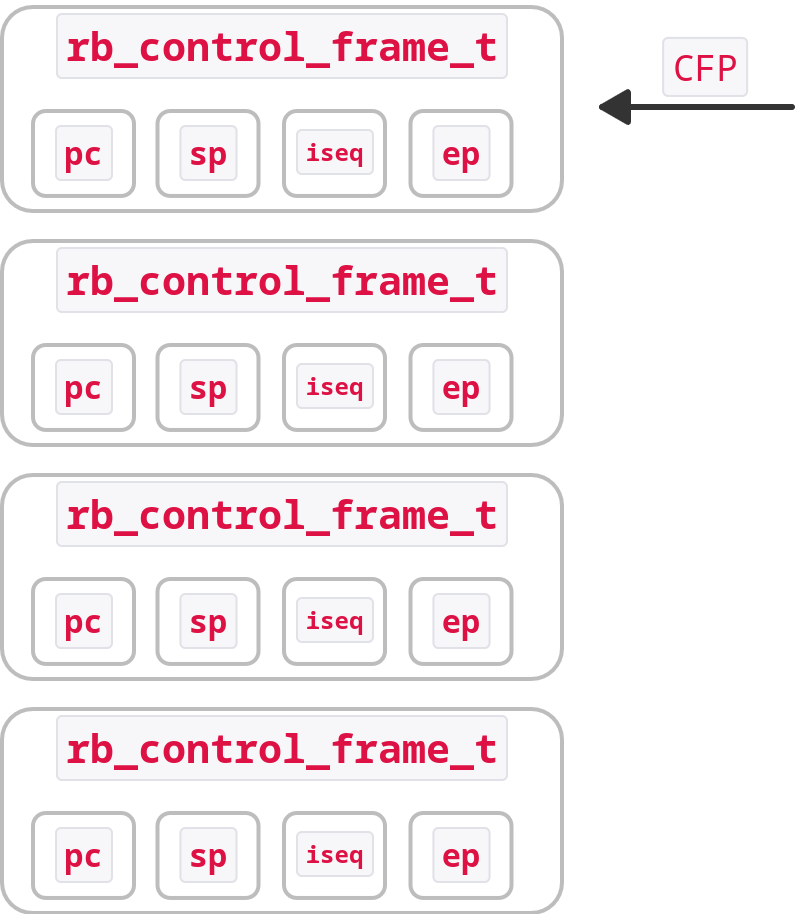

Inside of an execution context the control frame pointer points to the current control frame which is represented as a call stack we’re all familiar with as such:

So, if we have a pointer to the current control frame we can get access to our program’s stack which in turn tells us what is being executed. With that in mind, let’s take a look at the CFP for our deadlocked process:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

(gdb) call *(ruby_current_ec->cfp)

$3 = {

pc = 0x0,

sp = 0x7f23162300a8,

iseq = 0x0,

self = 139788671962360,

ep = 0x7f23162300a0,

block_code = 0x0,

__bp__ = 0x7f23162300a8,

jit_return = 0x0

}

Hmm, it doesn’t look quite right that the pc and iseq values are NULL pointers. pc being program counter and iseq instruction sequence. The struct definition is handy to reference for understanding these again. What’s going on here?

If we look into the ep (environment pointer) value we can see that its flags denote this control frame as a VM_FRAME_FLAG_CFRAME rather than a “Ruby frame.” This would track with how our program is calling sleep meaning control passes from Ruby code into an internal C function that in turn makes a syscall. Ruby has a function named VM_FRAME_RUBYFRAME_P which checks the flags on the environment pointer value to determine what type of frame it is. Using the following in GDB we can verify that it is considered a CFRAME by means of being a non-zero value from the bitwise AND operation which is the same operation that VM_FRAME_RUBYFRAME_P ends up performing through another function, VM_FRAME_CFRAME_P:

1

2

(gdb) call ruby_current_ec->cfp->ep[0] & VM_FRAME_FLAG_CFRAME

$4 = 128

That’s fine then, but how do we get a Ruby frame in that case? Because the stack is a contiguous block of memory, it’s easy enough to move up one control frame to inspect the previous frame by simply adding one byte to the pointer value as such:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

(gdb) call ruby_current_ec->cfp + 1

$5 = {

pc = 0x5571d53fa308,

sp = 0x7f2316230080,

iseq = 0x7f2316dfc880,

self = 139788671962360,

ep = 0x7f2316230078,

block_code = 0x0,

__bp__ = 0x7f2316230080,

jit_return = 0x0

}

We can also double check this frame’s type is Ruby code by getting the frame type from its environment pointer’s flags and comparing it to the frame type constants (values are printed in hex to more easily compare the constant values):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

# Frame type of the current control frame

(gdb) p/x ruby_current_ec->cfp->ep[0] & VM_FRAME_MAGIC_MASK

$6 = 0x55550001

# Frame type of the previous control frame

(gdb) p/x (ruby_current_ec->cfp + 1)->ep[0] & VM_FRAME_MAGIC_MASK

$7 = 0x11110001

# The current control frame matches the constant for a C function

(gdb) call (ruby_current_ec->cfp->ep[0] & VM_FRAME_MAGIC_MASK) == VM_FRAME_MAGIC_CFUNC

$8 = 1

# The previous control frame does /not/ match the constant for a C function

(gdb) call ((ruby_current_ec->cfp + 1)->ep[0] & VM_FRAME_MAGIC_MASK) == VM_FRAME_MAGIC_CFUNC

$9 = 0

# The previous control frame /does/ match the constant for a normal Ruby method

(gdb) call (ruby_current_ec->cfp->ep[0] & VM_FRAME_MAGIC_MASK) == VM_FRAME_MAGIC_METHOD

$10 = 0

The exact constant values and bit mapping for the flags are available in the vm_frame_env_flags enum.

But anyway, that control frame looks better now. It has a valid a program counter and instruction sequence pointer. Still though, how do we get that elusive line number to where our Ruby program stopped executing?

Tracking Down a Line Number

Inside the control frame, the instruction sequence value (iseq) is of particular interest since that holds the source location of the currently executing code. We can use this to track down what piece of Ruby code that control frame was executing. Indeed, if we print out the value of the iseq then we see an interesting struct named code_location:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

(gdb) call *((ruby_current_ec->cfp + 1)->iseq->body)

$11 = {

type = ISEQ_TYPE_METHOD,

iseq_size = 6,

iseq_encoded = 0x55a4e9d86c80,

[...snipped...]

location = {

pathobj = 140272768374920,

base_label = 140272768375800,

label = 140272768375800,

first_lineno = 3,

node_id = 6,

code_location = {

beg_pos = {

lineno = 3,

column = 0

},

end_pos = {

lineno = 5,

column = 3

}

}

},

[...snipped...]

So that’s it then?! Well, no. The beginning position is listed as line 3 and the end position listed as line 5. That corresponds with the foo method in our sleep.rb program, but not the specific line the sleep call is on. This struct instead represents the scope or block that Ruby is executing in. In order to get the line number of the current line of code we have to do a bit more work and call the rb_vm_get_sourceline function:

1

2

(gdb) call rb_vm_get_sourceline(ruby_current_ec->cfp + 1)

$12 = 5

Hey, that was easy! Line 5 indeed corresponds to the sleep call so we know we’re at the right place now. But how did rb_vm_get_sourceline get that from just the control frame pointer? Many of the helper functions that rb_vm_get_sourceline utilizes are inlined so we can’t easily call them directly in GDB. What it boils down to though is that Ruby will do some pointer math with the current program counter pointer and the pointer to the encoded instruction sequence to calculate a position offset and then read into a bit-vector that represents the specific instruction we’re interested in. The relevant definition of this bit-vector can be found in the iseq.c file, but a fair warning that it is heavy on the bitwise operations. The short of it is that this function will pull out the relevant iseq_insn_info_entry struct and then from there it can easily read the line_no field.

Getting a File Name

We have a line number now, but that’s only half of the puzzle. In order to make sense of this we also need to know what file that line number refers to. In this case it’s simple because we only have one file, but let’s pretend that we have a bunch of source files and don’t know which one to look at. How do we get the file name?

If we jump back to the iseq body print output from above, there’s a pathobj field inside the location struct. From the definition of this struct we know that this is either a string or an array with two elements, the relative and absolute path, to the source code file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

typedef struct rb_iseq_location_struct {

VALUE pathobj; /* String (path) or Array [path, realpath]. Frozen. */

VALUE base_label; /* String */

VALUE label; /* String */

int first_lineno;

int node_id;

rb_code_location_t code_location;

} rb_iseq_location_t;

Before we get into what’s inside that pointer we need to take one more detour first and discuss how Ruby represents strings and arrays internally. The strings and arrays in this case are not your run of the mill C strings & arrays but rather Ruby’s wrappers around them. That is, the internal data structure it uses to store your string when you create one in a Ruby program.

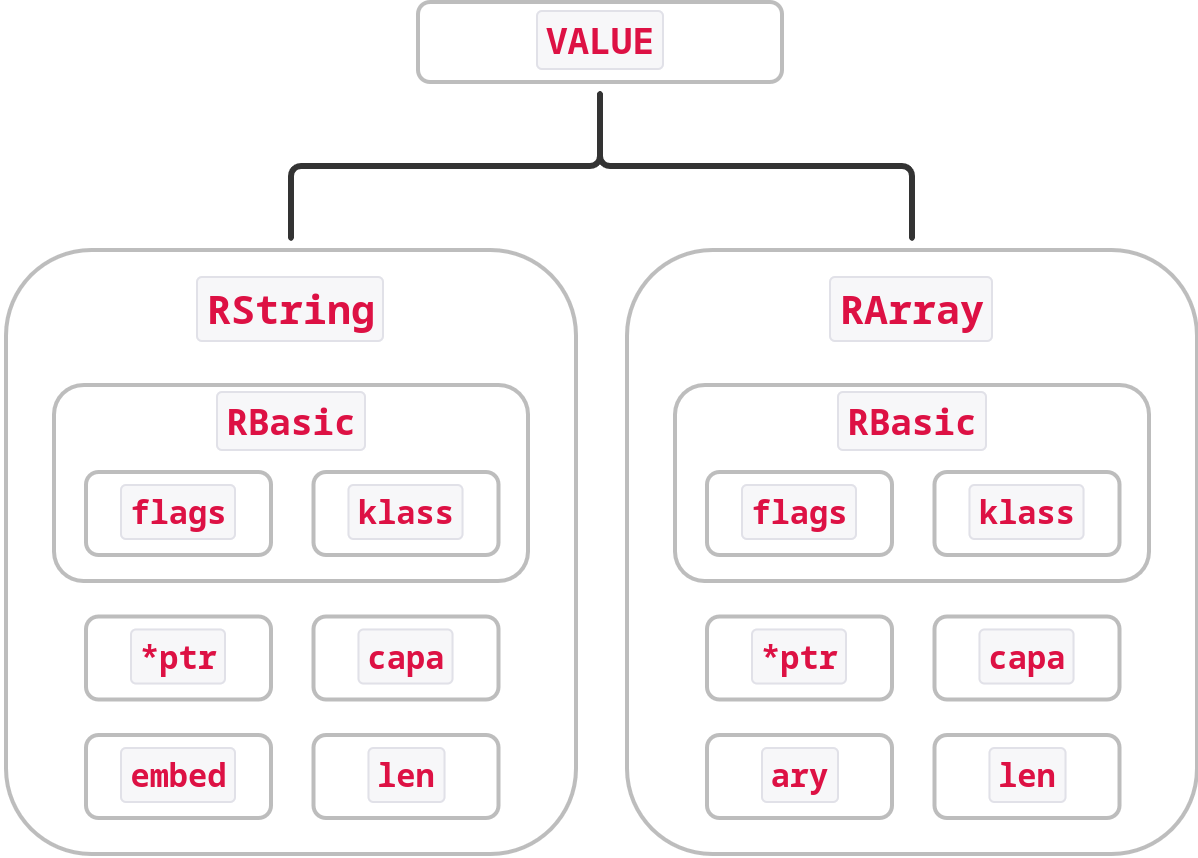

These are represented in Ruby through the RString and RArray structs. The struct definitions of each of these are well commented and have some handy info to help understand them better. What we need to know for our purposes here though is two fold:

RStringandRArrayhave optimizations where for small strings/arrays the values of those strings/arrays will be stored in the struct directly rather than using a pointer to a separate block of memory (embed/arybelow rather thanptr). As we’ll see further below, the filenames used in this example fall under that size limit. But if you’re replicating this and have a filename of sufficient length the actual content of the string may be in a slightly different location.- All of Ruby’s internal object representations include a struct called

RBasicwhich holds information about the class it represents and some flags. In effect, internally Ruby objects look something like the following diagram:

With that said, let’s just jump into getting the filenames:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# Relative path:

(gdb) call (char*)(

(struct RString*)(

(struct RArray*)(

ruby_current_ec->cfp+1).iseq->body.location.pathobj

).as.ary[0]

).as.embed.ary

$12 = 0x7faedac1cf50 "sleep.rb"

# Absolute path:

(gdb) call (char*)(

(struct RString*)(

(struct RArray*)(

ruby_current_ec->cfp+1).iseq->body.location.pathobj

).as.ary[1]

).as.embed.ary

$13 = 0x7faed9f5a0d8 "/tmp/sleep.rb"

And there’s our filename! But, whew, that’s quite the reach into a data structure there. Let’s break that down.

- First, we get the

pathobjpointer from theiseqlocation struct withruby_current_ec->cfp+1).iseq->body.location.pathobj. This part should be fairly familiar by now. - Next, we know from the Ruby source comment that this pointer is either an

RStringor anRArrayso we need to tell GDB how to interpret the memory it points to. In this case, it’s anRArray. - Then, as mentioned above, the array values are small enough to be embedded in the

RArraystruct directly so theas.ary[0]field is read. This is another pointer; this time to anRString. - Lastly, we again need to cast it to an

RStringand then we can read its embedded value,as.embed.ary. One more cast to a plain ‘olechar*gets the final string value of the source’s filename.

Before wrapping up, let’s take a quick look at the representation of the RArray and RString values to see how they compare to the diagram of these structs from above:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

# RArray:

(gdb) p/x *((struct RArray *)(ruby_current_ec->cfp+1).iseq->body.location.pathobj)

$14 = {

basic = {

flags = 0xa00012807,

klass = 0x7f42be3514b8

},

as = {

heap = {

len = 0x7f42bee9ce80,

aux = {

capa = 0x7f42b9a4a008,

shared_root = 0x7f42b9a4a008

},

ptr = 0x0

},

ary = {0x7f42bee9ce80}

}

}

# RString:

(gdb) p/x *((struct RString*)((struct RArray*)(ruby_current_ec->cfp+1).iseq->body.location.pathobj).as.ary[0])

$15 = {

basic = {

flags = 0xa20500805,

klass = 0x7f42be35ed98

},

as = {

heap = {

len = 0xe,

ptr = 0x6c732f656e616873,

aux = {

capa = 0x62722e706565,

shared = 0x62722e706565

}

},

embed = {

len = 0xe,

ary = {0x73}

}

}

}

The two structs here are fairly similar with the embedded ary and embed fields. If the value is too large for those then the heap field is used instead. Of course, the values in here are mostly pointers or junk values, but nevertheless it’s an interesting look into the internal data structures that back your strings and arrays when using them in Ruby-land.

There are endless more rabbit holes to go down for further exploration into Ruby’s internals here, but at this point we’ve accomplished the goal of peering inside of a running Ruby process from GDB to see what it is executing which makes for a good stopping point. This is barely scratching the surface of how Ruby executes your code. If this topic is interesting and you’re looking for further reading, Pat Shaughnessy’s book Ruby Under a Microscope does an excellent job of covering all of the nitty gritty details on Ruby’s implementation. It targets Ruby 1.9 & 2.0 which are fairly dated now, but the core concepts remain the same making it definitely still worth the read.