Over two years have passed since I’ve done any significant development on my encrypted chat program, Cryptully. In that time, a few issues with it have arisen and some issues were left outstanding from when development ramped down. Some of the larger items that needed to be addressed were:

- Most severe: The SMP MITM attack detection implementation was ironically vulnerable to MITM attacks.

- The hard coded DH prime was not uniquely generated.

- The tests have been failing for over two years.

- There was no way to for the server to determine what version of the program a client was running.

- The documentation for running and building the program had become out of date.

I have never gone back to a project after such a long period of time to fix bugs and add new features. Overall, I was pleasantly surprised at how well the code had aged after being neglected for two years. That is, everything still worked with the most recent versions of the libraries and frameworks I used and there were only a few spots where I wondered what the hell I was thinking when I wrote that code. However, there were a few challenges in fixing some of the long standing issues outlined above.

Fixing the SMP MITM detection

OTR (off-the-record) messaging utilizes the Socialist Millionaire Protocol to detect (not prevent) MITM attacks. I added this same feature to the Cryptully protocol, but with a critical flaw. The SMP replies on both parties having a pre-existing shared secret. In Cryptully’s first implementation, the key derived from the Diffie-Hellman exchange was used as the shared secret. At first this may seem reasonable because the secret negotiated as part of a DH exchange is never transmitted between the two endpoints. However, DH is susceptible to MITM attacks. Therefore, if an attacker does a MITM attack during the DH exchange, the key is now known to the attacker. Then when the the clients verify their connection with the SMP, the attacker is able to cause a false positive because he knows the secret being used! To make matters worse, this wasn’t just a theoretical problem, someone reading my blog emailed me a proof of concept program which successfully subverted the SMP implementation in Cryptully.

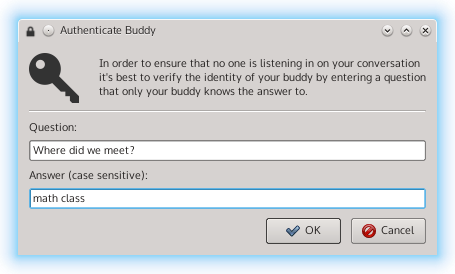

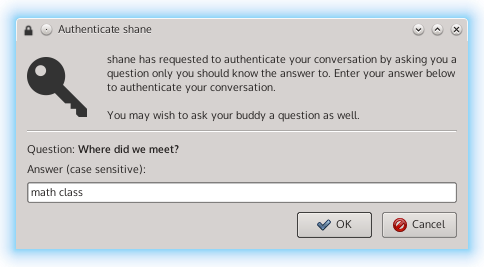

The good news was that my implementation of the SMP appeared to be correct. The problem was simply that I was using a secret that could be known to an attacker. The solution here was to ask the user for a secret to use instead of using the DH key. Unlike many secure connections, there is a advantage when dealing with a chat program. By its nature, the two people chatting are most likely familiar with one another. Thus, they should know something unique to their relationship that can be used as a secret. For example, one may ask how they first met or other some personal information unique to them. The answer to the user provided question is used as the shared secret in the SMP.

All said and done, the UI now looks something like this:

There is one problem with this approach, however: SMP compares integers, not strings. The answer provided by the user would have to be mapped to an integer. The obvious way to do this is to build an integer out of each character’s ASCII value. But is this correct? The scary part of doing crypto is that making assumptions like I was doing with this string to integer mapping can have disastrous consequences if that assumption turns out to be false. I needed to defer to OTR’s SMP implementation to validate this assumption.

After crawling through OTR’s source for a bit, I found the otrl_sm_step1 function which is where the SMP secret is taken from a string and mapped to an integer. Specifically, line 642 of sm.c (commit 9a90e5e) is:

1

gcry_mpi_scan(&secret_mpi, GCRYMPI_FMT_USG, secret, secretlen, NULL);

We can see that secret is being passed to Libgcrypt’s gcry_mpi_scan function. Reading through the Libgcrypt source led me to the _gcry_mpi_set_buffer function which is where the buffer passed to gcry_mpi_scan (in this case, a char array) is translated into an integer. Turns out that essentially all it is doing is what I anticipated, using the ASCII value of each character to construct an integer. Which is great because this is trivial to implement. To ensure my Python implementation was correct, I extracted the logic of the _gcry_mpi_set_buffer function to a short C program so I could check if the integer calculated from a given string matched.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

unsigned long _gcry_mpi_set_buffer(const void *buffer_arg, unsigned int nbytes);

int main(void) {

char *str = "Hello";

unsigned long num = _gcry_mpi_set_buffer(str, strlen(str));

printf("%lu\n", num);

return 0;

}

unsigned long _gcry_mpi_set_buffer(const void *buffer_arg, unsigned int nbytes) {

const unsigned char *buffer = (const unsigned char*)buffer_arg;

const unsigned char *p;

unsigned long alimb;

for(p = buffer+nbytes-1; p >= buffer+8;) {

alimb = (unsigned long)*p--;

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 8;

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 16;

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 24;

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 32;

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 40;

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 48;

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 56;

}

if(p >= buffer) {

alimb = (unsigned long)*p--;

if(p >= buffer) {

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 8;

}

if(p >= buffer) {

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 16;

}

if(p >= buffer) {

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 24;

}

if(p >= buffer) {

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 32;

}

if(p >= buffer) {

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 40;

}

if(p >= buffer) {

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 48;

}

if(p >= buffer) {

alimb |= (unsigned long)*p-- << 56;

}

}

return alimb;

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

string = 'Hello'

num = 0

shift = 0

for char in reversed(string):

num |= ord(char) << shift

shift += 8

print(num)

Admittedly, my Python implementation isn’t nearly as robust as the Libgcrypt implementation, but it gets the job done. With this function in place, it became possible to use a string as the SMP secret which resolved the MITM vulnerability.

Changing the DH Prime

Cryptully uses a Diffie-Hellman key exchange to establish a key to use for AES encryption. In October 2015, Alex Halderman and Nadia Heninger and Bruce Schneier wrote about a theory on how the NSA is breaking DH exchanges. A DH exchange relies on the two endpoints agreeing upon a prime number. As Halderman and Heninger explained, it seemed okay for everyone to use the same prime number. However, if an attacker is able to invest a large amount of time in cracking a given prime, any exchange that uses that prime will be vulnerable. It is hypothesized that the NSA has done this with the more “popular” primes.

Cryptully is no different in this regard; I remember looking for a prime that was widely used when I was writing the crypto portion of Cryptully years ago. Hence, I figured it would be a good idea to compute my own prime for use in Cryptully. Fortunately, OpenSSL makes this a relatively easy process.

1

$ openssl dhparam -out dh4096.pem 4096

The above command will search for a 4096-bit safe prime. This will take a significant amount of time to complete. My time was around 15 minutes, but it could be longer or shorter depending on hardware and luck. The default is to generate 2048-bit safe prime which is quite faster than 4096. You can also skip the safe prime and use a regular old prime by adding -dsaparam. Since this is something that is done infrequently, I decided to take the time to generate a 4096-bit safe prime.

The problem now becomes that OpenSSL generated this prime in a PEM file, which I could parse each time the program starts, but it seems a bit silly to read a file each time just to get what is essentially a hardcoded constant. Running the following will read PEM file and print the actual prime that was found:

1

$ openssl dh -in dh4096.pem -text

In my case, this is the prime that Cryptully now uses:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

DH Parameters: (4096 bit)

prime:

00:a5:3d:56:c3:0f:e7:9d:43:e3:c9:a0:b6:78:e8:

7c:0f:cd:2e:78:b1:5c:67:68:38:d2:a2:bd:6c:29:

9b:1e:7f:db:28:6d:99:1f:62:e8:f3:66:b0:06:7a:

e7:1d:3d:91:da:c4:73:8f:d7:44:ee:18:0b:16:c9:

7a:54:21:52:36:d4:d3:93:a4:c8:5d:8b:39:07:83:

56:6c:1b:0d:55:42:1a:89:fc:a2:0b:85:e0:fa:ec:

de:d7:98:3d:03:88:21:77:8b:65:04:10:5f:45:5d:

86:55:95:3d:0b:62:84:1e:9c:c1:24:8f:a2:18:34:

bc:9f:3e:3c:c1:c0:80:cf:cb:0b:23:0f:d9:a2:05:

9f:5f:63:73:95:df:a7:01:98:1f:ad:0d:be:b5:45:

e2:e2:9c:d2:0f:7b:6b:ae:e9:31:40:39:e1:6e:f1:

9f:60:47:46:fe:59:6d:50:bb:39:67:da:51:b9:48:

18:4d:8d:45:11:f2:c0:b8:e4:b4:e3:ab:c4:41:44:

ce:1f:59:68:aa:dd:05:36:00:a4:04:30:ba:97:ad:

9e:0a:d2:6f:e4:c4:44:be:3f:48:43:4a:68:aa:13:

2b:16:77:d8:44:24:54:fe:4c:6a:e9:d3:b7:16:4e:

66:03:f1:c8:a8:f5:b5:23:5b:a0:b9:f5:b5:f8:62:

78:e4:f6:9e:b4:d5:38:88:38:ef:15:67:85:35:58:

95:16:a1:d8:5d:12:7d:a8:f4:6f:15:06:13:c8:a4:

92:58:be:2e:d5:3c:3e:16:1d:00:49:ca:bb:40:d1:

5f:90:42:a0:0c:49:47:46:75:3b:97:94:a9:f6:6a:

93:b6:74:98:c7:c5:9b:82:53:a9:10:45:7c:10:35:

3f:a8:e2:ed:ca:fd:f6:c9:35:4a:3d:c5:8b:5a:82:

5c:35:33:02:d6:86:59:6c:11:e4:85:5e:86:f3:c6:

81:0f:9a:4a:bf:91:7f:69:a6:08:33:30:49:2a:ed:

b5:62:1e:bc:3f:d5:97:78:a4:0e:0a:7f:a8:45:0c:

8b:2c:6f:e3:92:37:75:41:9b:2e:a3:5c:d1:9a:be:

62:c5:00:20:df:99:1d:9f:c7:72:d1:6d:d5:20:84:

68:dc:7a:9b:51:c6:72:34:95:fe:0e:72:e8:18:ee:

2b:2a:85:81:fa:b2:ca:f6:bd:91:4e:48:76:57:3b:

02:38:62:28:6e:c8:8a:69:8b:e2:dd:34:c0:39:25:

ab:5c:a0:f5:0f:0b:2a:24:6a:b8:52:e3:77:9f:0c:

f9:d3:e3:6f:9a:b9:a5:06:02:d5:e9:21:6c:3a:29:

99:4e:81:e1:51:ac:cd:88:ea:34:6d:1b:e6:58:80:

68:e8:73

generator: 2 (0x2)

And there’s a nice, long hex number that can be dumped into a constant in the crypto class.

Still though, I wanted to do due diligence on this prime number. Was it actually prime? Surely, we could write a quick program to do a primality test on it. My first attempt was an extremely simple Python script:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

def isprime(x):

for i in range(2, x-1):

if x % i == 0:

return False

else:

return True

print(isprime(0x00a53d56c30fe79d43e3c9a0b678e87c0fcd2e78b15c676838d2a2bd6c299b1e7fdb286d991f62e8f366b0067ae71d3d91dac4738fd744ee180b16c97a54215236d4d393a4c85d8b390783566c1b0d55421a89fca20b85e0faecded7983d038821778b6504105f455d8655953d0b62841e9cc1248fa21834bc9f3e3cc1c080cfcb0b230fd9a2059f5f637395dfa701981fad0dbeb545e2e29cd20f7b6baee9314039e16ef19f604746fe596d50bb3967da51b948184d8d4511f2c0b8e4b4e3abc44144ce1f5968aadd053600a40430ba97ad9e0ad26fe4c444be3f48434a68aa132b1677d8442454fe4c6ae9d3b7164e6603f1c8a8f5b5235ba0b9f5b5f86278e4f69eb4d5388838ef15678535589516a1d85d127da8f46f150613c8a49258be2ed53c3e161d0049cabb40d15f9042a00c494746753b9794a9f66a93b67498c7c59b8253a910457c10353fa8e2edcafdf6c9354a3dc58b5a825c353302d686596c11e4855e86f3c6810f9a4abf917f69a6083330492aedb5621ebc3fd59778a40e0a7fa8450c8b2c6fe3923775419b2ea35cd19abe62c50020df991d9fc772d16dd5208468dc7a9b51c6723495fe0e72e818ee2b2a8581fab2caf6bd914e4876573b023862286ec88a698be2dd34c03925ab5ca0f50f0b2a246ab852e3779f0cf9d3e36f9ab9a50602d5e9216c3a29994e81e151accd88ea346d1be6588068e873))

After waiting about five minutes for this function to return, I realized that a 4096-bit prime was too large to test with such a naive method. But this is exactly the type of task OpenSSL is built for. Surely it could do a primality test on this number.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

#include <stdio.h>

#include <openssl/bn.h>

int main(void) {

char *p_str = "00a53d56c30fe79d43e3c9a0b678e87c0fcd2e78b15c676838d2a2bd6c299b1e7fdb286d991f62e8f366b0067ae71d3d91dac4738fd744ee180b16c97a54215236d4d393a4c85d8b390783566c1b0d55421a89fca20b85e0faecded7983d038821778b6504105f455d8655953d0b62841e9cc1248fa21834bc9f3e3cc1c080cfcb0b230fd9a2059f5f637395dfa701981fad0dbeb545e2e29cd20f7b6baee9314039e16ef19f604746fe596d50bb3967da51b948184d8d4511f2c0b8e4b4e3abc44144ce1f5968aadd053600a40430ba97ad9e0ad26fe4c444be3f48434a68aa132b1677d8442454fe4c6ae9d3b7164e6603f1c8a8f5b5235ba0b9f5b5f86278e4f69eb4d5388838ef15678535589516a1d85d127da8f46f150613c8a49258be2ed53c3e161d0049cabb40d15f9042a00c494746753b9794a9f66a93b67498c7c59b8253a910457c10353fa8e2edcafdf6c9354a3dc58b5a825c353302d686596c11e4855e86f3c6810f9a4abf917f69a6083330492aedb5621ebc3fd59778a40e0a7fa8450c8b2c6fe3923775419b2ea35cd19abe62c50020df991d9fc772d16dd5208468dc7a9b51c6723495fe0e72e818ee2b2a8581fab2caf6bd914e4876573b023862286ec88a698be2dd34c03925ab5ca0f50f0b2a246ab852e3779f0cf9d3e36f9ab9a50602d5e9216c3a29994e81e151accd88ea346d1be6588068e873";

BIGNUM *p = BN_new();

BN_hex2bn(&p, p_str);

printf("%d\n", BN_is_prime(p, BN_prime_checks, NULL, NULL, NULL));

BN_free(p);

return 0;

}

This approach finished running almost instantaneously with an unsurprising result of: yes, it was prime. Great, all that was left was to replace the existing prime used in Cryptully with this new one and problem solved!

Writing Passing Tests

Ever since I stopped major work on Cryptully the tests have been failing. Every time I pushed a minor change to the repo Travis was quick to pop up in my inbox to remind me of this fact. The trouble was that the existing tests were long neglected and did not work at an architectural level with the rest of the program. They were also very limited in scope and essentially useless. Because of this I decided it was best to throw them out and start over.

My new goal was to write a very basic test that started a server and two clients and had those two clients start a chat session with one another. Being a program that no one used anymore, it seemed like a waste of time to write in depth tests. A high level integration test would signal if any of the core components of the program were broken. This should be simple enough, right? Well, if it were, I wouldn’t be writing this.

My first attempt was to stay within Python’s testing framework, start a mock server thread and then connect a mock client to it. This quickly proved problematic because the client relied on a series of callbacks to handle events from the server. Some quick searching lead me to the Mock library. The problem was that its assertions expected the callback to have been called when the assertion was called rather than waiting for it to be called. Seeing as I was trying to test server-client communication, I didn’t have the luxury of being able to rely on any specific timing. However, it was easy enough to wrap the Mock object with one that waited for callback to be called within a certain timeout period.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

class WaitingMock(Mock):

TIMEOUT = 3

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

super(WaitingMock, self).__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self.calledEvent = Event()

def _mock_call(self, *args, **kwargs):

retval = super(WaitingMock, self)._mock_call(*args, **kwargs)

if self.call_count >= 1:

self.calledEvent.set()

return retval

def assert_called_with_wait(self, *args, **kargs):

self.calledEvent.clear()

if self.call_count >= 1:

return True

self.calledEvent.wait(timeout=self.TIMEOUT)

self.assert_called_with(*args, **kargs)

My implementation was based off of a feature request for the Mock library asking for the same functionality.

So now I was able to wait for a callback in an assertion. This worked well for testing server-client communication, but it got much more hairy when it came to testing client-client communication. Ideally I wanted to be able to do assertions from both clients, but this meant having to call assertions from two threads started from the test thread. Deadlocks and non-deterministic tests quickly arose making this approach not feasible.

Long story short, I tried a handful of different approaches, but ended up throwing out Python’s testing framework. I now had the ability to start three threads:

- Server

- Client 1

- Client 2

The mock server was relatively minimal and acted much like the real server, listening for incoming connections and relaying messages between clients. The mock clients are just threads that have a predefined behavior of how to communicate with each other; checking for certain events along the way. Such as, did client 1 send the message I expected? Did client 2 start typing and then stop typing? Did client 1 initiate an SMP request with this secret?

I did miss having the nice test output showing which tests passed and which failed, however. This was easy enough to implement myself by simply wrapping everything in the mock client thread’s run() method with a try & catch block which caught assertion failures and any other type of exception.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

try:

assertions...

except AssertionError as err:

self.failure()

self.exceptions.append((err, traceback.format_exc()))

except Exception as err:

self.exception()

self.exceptions.append((err, traceback.format_exc()))

After each test I would get the nice output of ., F, or E. And when all the tests were finished, I could print any assertion failures or other exceptions that were thrown so that they would be printed below the test results summary.

Overall, making my own free-form tests proved much more simple than trying to force multi-threaded tests into an existing testing framework. I’m sure there is a better solution out there, but this one works wonderfully for what I need it to do which is to act as a canary for something larger that has broken.

Conclusion & Reflections

First and foremost, it’s nice to have these longstanding issues finally resolved. Fixing them took roughly the level of time and effort I thought it would; at least there were no insurmountable surprises along the way. However, with these issues fixed, Cryptully will most likely fall back into disrepair for the foreseeable future as I don’t have much of a use for it anymore.

The original purpose of this project was as a learning exercise for myself in order to gain a better understanding of cryptography, protocol design, networking, cross-platform development, and UI design. Having learned a great deal from building this project, I’ve lost interest and moved on. There are much better alternatives out there and the last thing the world needs is yet another chat program.

For those that may be interested, the full source code is available on GitHub and the accompanying documentation is available on cryptully.com.