A few days ago I wrote a post about how to not go about writing an arbitrary precision data type in C to calculate pi. If you read the article, I talked about how a friend and I were trying to accomplish that task in 24 hours. Needless to say, it didn’t work and I resorted to using a library that was already available. Namely, MPFR. After a little research on Wikipedia about the best approximations to pi, and a couple of days of off and on work, I had a pretty good solution up and running.

First, let’s talk about the math behind this. There are a bunch of approximations to pi; some older, some newer, some faster, some slower. At first, I used Newton’s approximation to calculate pi.

This worked, but was slow (I didn’t record exact execution times). As everyone knows, factorials are huge numbers and grow very rapidly. In this case, the numbers were just too big to efficiently accomplish the task at hand. Could have I done something like Sterling’s approximation? Sure, but there’s better ways to calculate pi. No use in wasting time.

Next up, I gave the cubic convergence version of Borwein’s algorithm mainly because there were no factorials in it. This worked pretty well actually. It calculated pi within a reasonable amount of time (more details below), but because it was a recurrance, I would not be able to multithread it.

Now with multithreading in mind, I turned my attention to the 1993 version of Borwein’s algorithm, which was a summation.

On the up side, it was a summation, which is easy to multithread. On the downside, look at all those factorials. Long story short, I hit the same with this approach as I did with Newton’s approximation above; it worked, it was just too slow.

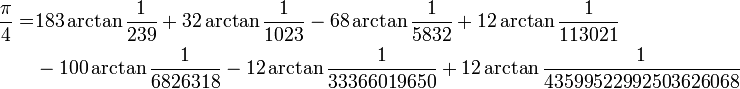

Finally, after some more research, I came across the approximation used by Yasumasa Kanada of Tokyo University to calculate pi to 1.24 trillion digits in 2002. If it was good enough for him, it must certainly be good enough for me. According to Wikipedia, this approximation by Hwang Chien-Lih in 2003 is the most efficient known approximation to pi:

Looks good to me! Best of all, it’s the summation of 7 different terms. This means I could do the work in 7 separate threads. Now to just code it up. We make extensive use of the MPFR functions. If you aren’t familiar with the library, all these functions are very well documented, although most of them should be obvious just by the name if you’re only reading the code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

void* calc_term(void* term_num) {

char x_str[22];

int op;

int coeff;

mpfr_t *term;

switch(*(int *)term_num) {

case 1:

term = &t1;

coeff = 183;

op = ADD;

sprintf(x_str, "239");

break;

case 2:

term = &t2;

coeff = 32;

op = ADD;

sprintf(x_str, "1023");

break;

case 3:

term = &t3;

coeff = 68;

op = SUB;

sprintf(x_str, "5832");

break;

case 4:

term = &t4;

coeff = 12;

op = ADD;

sprintf(x_str, "113021");

break;

case 5:

term = &t5;

coeff = 100;

op = SUB;

sprintf(x_str, "6826318");

break;

case 6:

term = &t6;

coeff = 12;

op = SUB;

sprintf(x_str, "33366019650");

break;

case 7:

term = &t7;

coeff = 12;

op = ADD;

sprintf(x_str, "43599522992503626068");

break;

default:

pthread_exit(NULL);

}

// Default precision is local to each thread so it must be specified here again

mpfr_t x;

mpfr_set_default_prec(precision);

mpfr_init_set_str(x, x_str, 10, MPFR_RNDN);

// t1 = 183 * atan(1/239)

// t2 = 32 * atan(1/1023)

// t3 = 68 * atan(1/5832)

// t4 = 12 * atan(1/113021)

// t5 = 100 * atan(1/6826318)

// t6 = 12 * atan(1/33366019650)

// t7 = 12 * atan(1/43599522992503626068)

mpfr_atan2(*term, one, x, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_mul_ui(*term, *term, coeff, MPFR_RNDN);

// Add the term to the sum

pthread_mutex_lock(&sum_mutex);

if(op == ADD) {

mpfr_add(pi, pi, *term, MPFR_RNDN);

} else {

mpfr_sub(pi, pi, *term, MPFR_RNDN);

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&sum_mutex);

// We're done with the current term and x value

mpfr_clears(*term, x, NULL);

mpfr_free_cache();

pthread_exit(NULL);

}

That’s really all there is to it. There first half of the function is selecting the proper numbers to use for the given term since there’s no use in having 7 slightly different functions.

The magic happens with these two lines:

1

2

mpfr_atan2(*term, one, x, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_mul_ui(*term, *term, coeff, MPFR_RNDN);

As per the formula above, they calculate the given term which is then added to the sum with:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

pthread_mutex_lock(&sum_mutex);

if(op == ADD) {

mpfr_add(pi, pi, *term, MPFR_RNDN);

} else {

mpfr_sub(pi, pi, *term, MPFR_RNDN);

}

pthread_mutex_unlock(&sum_mutex);

This is a good time to look at one of the concerns accounted for when using threads. If there is a sum variable which each term is added to and there are seven instances of this function running concurrently, what’s to prevent two or more of the threads from trying to add their results to the sum variable at the same time? That would cause a big problem! So, we use a mutex to only allow one thread at a time from accessing the sum variable.

A pitfall that I fell into was setting the precision of the mpfr_t variables. In the main function I specify how precise I want the number to be with:

1

mpfr_set_default_prec(precision);

From there every variable initialized after that would have that precision, except that is local to the current thread. This means that the precision needs set again each time a thread is created. That’s why this function is called again in the calc_term() function.

Another tricky part was determining the level of precision I needed mpfr to use in order to get the number of digits of pi I wanted. For example, if I wanted pi accurate to 1 million digits, I needed to tell mpfr to use ~3.35 million digits of precision. It seems natural to me that the one would call this program with the number of accurate digits wanted so experimentally I determined to multiply the precision given on the command line by 3.35 to get pi accurate to that number.

Finally, speaking of precision, how am I supposed to check our precise my approximation is? Well, some nice guys at MIT have a text file with the first 1 billion digits of pi. http://stuff.mit.edu/afs/sipb/contrib/pi/ After all the calculations are finished, the final approximation is converted into a (really long) string and is then compared against a given file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

unsigned long check_digits(char *pi) {

// If pi.txt exists, compare the digits

FILE *digits = fopen("pi.txt", "r");

char *buffer = malloc(CHUNK_SIZE);

size_t chunk_size;

unsigned long bytes_read = 0;

unsigned long accuracy = 0;

if(digits == NULL || buffer == NULL) {

return 0;

}

while(!feof(digits)) {

chunk_size = fread(buffer, 1, 100, digits);

if(ferror(digits)) {

fprintf(stderr, "Error while reading pi.txt.\n");

break;

}

// Compare the digits

for(unsigned int i=bytes_read, j=0; i<bytes_read+chunk_size; i++, j++) {

if(i > precision || buffer[j] != pi[i]) {

goto outer;

}

accuracy++;

}

bytes_read += chunk_size;

}

outer:

fclose(digits);

free(buffer);

buffer = NULL;

// Don't count the "3." as accurate digits

return (accuracy > 2) ? accuracy-2 : accuracy;

}

Relatively simple. fread() is used here since the input file is all one line so the typical way of reading a file line by line with fgets() is a bad idea. In fact, given that the output string could be very, very large (10 million or more characters), it would probably be best to write the output to a temporary file and then compare the two files with fread and two temporary buffers. But then again, assuming each digit is 1 byte, we could generate up to 1 billion digits and use 1gb of RAM to store all them, which is reasonable on a modern system. If I ever get to the point where I’m generating more than 1 billion digits, that should probably be changed.

The logic behind the recurrence method is very similar, just the math is different and it is not multithreaded. I’ll skip most of the details because it’s a slower method and not as interesting. The relevant part with the core of the recurrence relation is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

// a0 = 1/3

mpfr_set_ui(a1, 1, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_div_ui(a1, a1, 3, MPFR_RNDN);

// s0 = (3^.5 - 1) / 2

mpfr_sqrt_ui(s1, 3, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_sub_ui(s1, s1, 1, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_div_ui(s1, s1, 2, MPFR_RNDN);

unsigned long i = 0;

while(i < MAX_ITERS) {

// r = 3 / (1 + 2(1-s^3)^(1/3))

mpfr_pow_ui(tmp1, s1, 3, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_ui_sub(r, 1, tmp1, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_root(r, r, 3, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_mul_ui(r, r, 2, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_add_ui(r, r, 1, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_ui_div(r, 3, r, MPFR_RNDN);

// s = (r - 1) / 2

mpfr_sub_ui(s2, r, 1, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_div_ui(s2, s2, 2, MPFR_RNDN);

// a = r^2 * a - 3^i(r^2-1)

mpfr_pow_ui(tmp1, r, 2, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_mul(a2, tmp1, a1, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_sub_ui(tmp1, tmp1, 1, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_ui_pow_ui(tmp2, 3UL, i, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_mul(tmp1, tmp1, tmp2, MPFR_RNDN);

mpfr_sub(a2, a2, tmp1, MPFR_RNDN);

// s1 = s2

mpfr_set(s1, s2, MPFR_RNDN);

// a1 = a2

mpfr_set(a1, a2, MPFR_RNDN);

i++;

}

So… let’s run this thing. Keep in mind that I’m running these tests on a 2.475GHz (slightly overclocked) Core 2 Quad processor. This is a generation behind the current i3/5/7 processors and limits me to 4 cores to run threads on. I’m sure that a newer system would run these tests noticeably faster.

First off, let’s use the recurrence version to calculate the first 1 million digits of pi (the “test” target in the Makefile does this).

1

2

3

4

$ make test

./irrational --hide-pi 1000000

Time: 54 seconds

Accuracy: 1008443 digits

Just under a minute; not bad. Now let’s use the multi-threaded version.

1

2

3

4

$ make test

./irrational --hide-pi 1000000

Time: 21 seconds

Accuracy: 1008449 digits

21 seconds, awesome! These were compiled with the -O3 flag on so there’s not much more optimization I can request be done except run it on a faster system. Let’s try 10 million digits now.

First with the recurrence method:

1

2

3

$ ./irrational --hide-pi 10000000

Time: 818 seconds

Accuracy: 10084495 digits

Just under 14 minutes. Not too shabby, but what about when multi-threading it?

1

2

3

$ ./irrational --hide-pi 10000000

Time: 432 seconds

Accuracy: 10084503 digits

7.2 minutes. That’s much, much faster. Just for fun I decided to see how long the same calculation would take with compiler optimization turned off.

1

2

3

$ ./irrational --hide-pi 10000000

Time: 655 seconds

Accuracy: 10084503 digits

10.9 minutes. That’s a big difference. Just goes to show how powerful compiler optimization can be. Thanks GCC!

2013 Update: Since I first wrote this I upgraded my CPU to an i7-4770K which was considerably faster given the ability to run all seven threads simultaneously.

1

2

3

$ ./irrational --hide-pi 10000000

Time: 136 seconds

Accuracy: 10084503 digits

2021 Update: I upgraded my 2013 hardware this year to a Ryzen 5900X CPU and wanted to see how this program behaved with the new hardware. It has become an interesting benchmark to check after each new generation of hardware over close to 10 years now. Not that it’s unexpected, but it’s satisfying to see a program that took 7 minutes in 2012 now take under 1 minute to run.

1

2

3

$ ./irrational --hide-pi 10000000

Time: 42 seconds

Accuracy: 10084503 digits

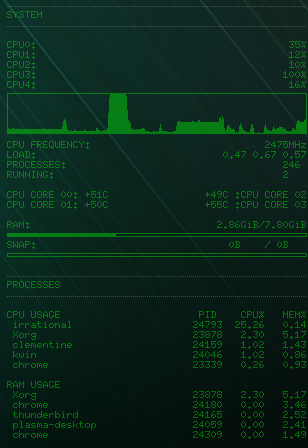

Lastly, as a little experiment to see how the threads were behaving, I took a few screenshots of my Conky system monitor while the program was running. With a single thread on a quad core system, as you would expect, exactly one core was running at 100%.

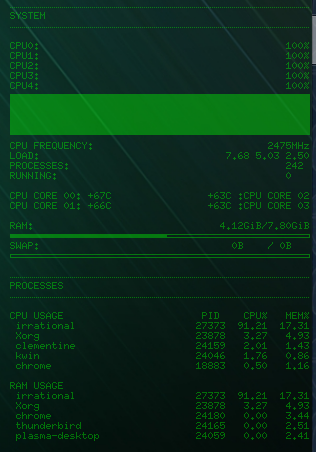

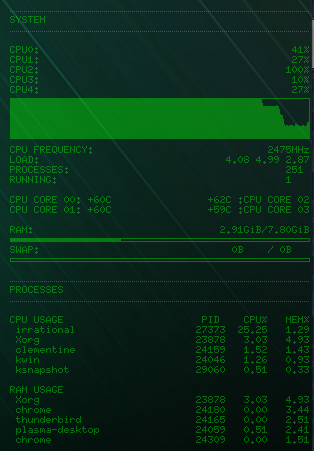

The multi-threaded CPU and RAM usage is more interesting. All four cores are running at 100% (and getting pretty hot as well).

It’s also eating up a bunch of RAM (17%). The highest I saw it go was 19% which tells me, given enough time, I could calculate more than 10 million digits of pi on this system. I also found it interesting to watch the CPU usage as the threads finished and the CPU usage dropped to 25% again.

So that’s my foray into calculating very precise numbers. It’s a project I’ve been wanting to work on for a while and certainly learned a lot from it. As always, the code is open source and available on GitHub at https://github.com/shanet/Irrational with instructions for compiling and running it in the readme.